|

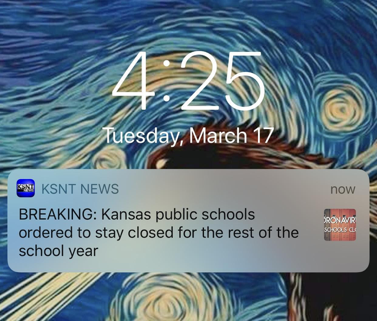

by John Ritchie I started the 2019-2020 school year--my 20th year in the classroom--with more optimism and excitement than usual. I loved both of my PLCs. The junior PLC was hoping to breathe new life into Miller’s Death of a Salesman by pairing it with Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. Second semester, we were ready to roll out (and defend if necessary) The Perks of Being a Wallflower. These literature units would alternate with our renewed pumped up approach to digital literacy and research writing. My senior composition PLC was likewise pushing new citation styles and trying to help students see how and why the different citation styles were applied. Amidst all of this, a friend from Washburn University asked if I would sponsor a future teacher’s observation hours. If all went well, I would mentor ST the following fall during her student teaching semester. I would be open to all of her questions through fall, winter, and spring as we then geared up to an experience none of us could anticipate. ST’s 2019 fall semester experience went very well. Initially, I would preview the lesson plans for her and then have her come up with questions about anything she observed during her two-hour stay. . Most of the questions were about the classroom layout, why I addressed some behaviors but ignored others, and how the transactions of the day would affect what I did tomorrow. When we got to our junior plays, she knew the classes she was observing well enough to predict that they would hate Biff and Happy (bunch of losers) but love Walter and Beneatha’s spirit. By the end of the semester, she was practicing electronic feedback on essays and creating seating charts based on what she knew about the students. I was pleased with her progress, so I was happy to put in the paperwork to be her mentor for Fall 2020. I kept in touch with ST throughout the beginning of this past spring semester.. I shared our materials as we put together a tougher research unit than we’d ever done with our juniors. She previewed materials and began to see the delicate balance of creating clear objectives in student-friendly language. When our PLC spent three days wordsmithing a heads up for parents about The Perks of Being a Wallflower, she and I talked through the professional changes the team had made from the first to the final draft. With Part I of Perks completed without controversy just before spring break, I said things would be boring enough that she should focus on her final university classes and check back with me in May. We all know how quickly things changed during spring break. ST contacted me to ask what we were doing. All I could say was “we’re adapting.” It was tough to keep her informed when my own information seemed to change by the minute. Then came the press conference. All of us in education had an inkling of what would happen, but I doubt any of us believed it. When the words were said, I couldn’t accept it. I jumped as my breaking news alert confirmed it. Dazed, I captured the screenshot for posterity: Another alert--a text from ST: “Are you watching? What do you think?” I felt an obligation to be the mentor. A temptation to sit above it all and try to remain objective. But I found I didn’t have the energy or desire. It didn’t feel right. I was watching the press conference blinking back tears because one of the best parts of my life had been taken away for at least the next six months. “Devastated,” I replied. As ST continued to check in periodically with me, I wondered how I could continue to offer myself as a mentor to her. I was dealing with Google Meetings that were attended by less than 10% of my classes. Incidents of plagiarism began to spike. It became a vicious cycle of my kids’ motivation dying, which hurt mine, which no doubt hurt my kids, and downward we went. I felt like nothing I did mattered. The assignments and the grading became busy work. What could she learn from someone who no longer felt effective? I will never be more thankful for my PLC colleagues than I was from March - May 2020. It was easily one of the lowest points of my teaching career, but they helped me survive it. Our weekly meetings were the only confirmation I had that I was not alone, that I was not failing as a professional, and that we were all clawing toward a finish line hoping to have something to be proud of at the end. As the school year wrapped up, my PLCs made a Google Form reflection for our students that we counted as the last assignment of the semester. We asked students to be honest about what worked for them and, in a worst case scenario, what should change if we had to go through this again next fall. Some of my worst fears were confirmed--the students saw some of what we did as boring busy work--but we also received encouragement saying they thought we did the best we could under the circumstances. One thing I noticed was how many students said they appreciated the ongoing contacts, even if the students did not engage us in return. There were also many genuine messages about how much they enjoyed and missed our class. That helped me realize that any successes we had in the fourth quarter were from the relationships we had built the previous seven months. It also helped me realize that I could continue as a mentor for ST by building off the relationship we had created last year, and by welcoming her as a colleague into our PLC. ********** It’s now late June. ST has finished her PLT and is beginning to ask questions about the fall. During any other year, we would approach it the same way I usually approach the fall and reflect upon on the previou year: identify what worked and what we can do to improve upon it; identify what bombed and evaluate if it is worth salvaging it,;and identify what new learning has excited me in the past year and where I can implement it. Of course we can still go through this process and build on the foundation created from last year, but the pandemic remains the inescapable elephant in the room. We cannot plan for it. Instead of giving in to the despair I felt earlier, I tell her it is an opportunity to dive deeper into what teachers and students in our district, and across the state, are already using. As we are a Google school, one priority is making sure she is proficient with Google Classroom and Forms. We look at screencast software and search teacher sites for the most user-friendly resources. I give her National Writing Project books and links to sites like KATE and NCTE’s ALAN site. The exchange flows both ways. As someone who is only five or six years older than our students, she is more likely to know what technology will be most engaging to them without seeming forced or, dare I say it, cringe. Part of her job is to suggest whatever she thinks might help us engage our students. She floats the idea of a Tik-Tok for our classes. I am not yet convinced, but I am listening. Now we get together at least once a week to walk a public trail and talk about the fall. We get past our anxieties by discussing education developments. We joke that our walks in the summer humidity will give us the endurance to teach eight hours while wearing a mask. Many Board of Regents schools have announced that on-campus classes will end with Thanksgiving break. Will that happen to us? We know it’s possible. Based on the 4th quarter, we decided to suggest to the PLC that we put the major work in the 1st quarter. It may be an illusion of control, but the discussions help us acknowledge the challenges that lay ahead. Relationship-building is our top priority. Our first assignment together is to come up with a plan to build connections with students as soon as we are able to contact them, regardless of what that contact might look like. I still worry whether I’ll be an effective mentor for ST. Even under ideal conditions, student teaching is an unpaid internship with all of the stress of teaching without many of the benefits. She is entering a situation that turned us all into first-year teachers again. This year her questions will often be the questions I’m trying to answer, too. The best that I can do is to acknowledge my own doubts, but show how we push past them through continuous learning and flexibility. I will show her how to enter a career that often thrives on adapting to crises whether it is school violence, sudden changes in curriculum, or even a pandemic.  About the Author About the author: John Ritchie lives in Topeka where he teaches English 11 and Composition at Washburn Rural High School, and Composition as an adjunct professor at Washburn University. He has been an active member of KATE for 15 years. Facebook: John Ritchie Instagram: @mr_jritchie

2 Comments

By Nathan Whitman When I became employed at my first and present job as an English teacher in 2012, I knew that I was in for a culture shock. I had graduated from a 6A KSHSAA (Kansas State High School Activities Association) division high school of more than 2,000 students, and now I was going to teach in a 1A school of a few more than 200. However, upon having one of my first meetings with a school employee, I realized that Burrton was in for an equally stark culture shock from me. I’d read the state data reports. I knew that the majority of my students would be white. I knew that a handful were of various minority and cultural groups. Nevertheless, when I inquired of a staff member about how many students in the school were LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning) and if there was a GSA (gender and sexuality alliance), I was told, “We don’t have gay students at this district.” With that perspective – no wonder! I was certain that these kids did not feel like they had a welcoming culture to be themselves. Clearly, this “educator” either did not know, did not care, or chose to be in denial of the hard fact that 4.5% of Americans are LGBTQ, and that number represents only the self-reporting to a Gallup poll. Those in the closet are surely even greater in rank. In my head I’d done the numbers: at a school of around 250 individuals (staff and students) – and I may be rounding up – 11-12 had to be LGBTQ in a given year. Knowing those statistics, I was determined to chop that closet door down: Here’s Johnny! Throughout the course of my studies at Wichita State University, not only did I become certain of my career path as an English educator, I also realized that as much as I wanted to be a queer role model for my students and ally, I still had to play my cards carefully and closely to the chest. At the time, Kansas had no workplace protections for LGBTQ individuals unless they were written into the employment nondiscrimination clause (to no one’s surprise: sexual orientation was not and still is not covered by many districts’ contract language – my own included). Furthermore, with Kansas being an at-will state, I’d have to document anything I did in support of LGBTQ students or advocacy for myself (for legal reasons), as I could – and still can – be terminated from my job at my employer’s whim with no reasons given. While the at-will language states that “your employer can fire you for any non-discriminatory and/or non-retaliatory reason,” unless I had proof that my firing was discriminatory or retaliatory, I would and still can be sunk. This blog post could even be cause for termination, and I’d never know. Luckily, I’ve had fantastic administrative support, but I know that others are not so lucky. I would like to think that LGBTQ educators can feel more at ease with their own personal lives and advocacy of LGBTQ students as of June 16, 2020, which is when I am writing this new draft of this blog post. For those unaware, in an unprecedented motion, two conservative Supreme Court justices sided with the four liberal that Title VII protects LGBTQ employees from workplace discrimination and termination. Hooray! I can now put up a picture of my husband and me after our wedding this summer and not be fired – I hope. I preface the core of my post with these anecdotes and current events because we LGBTQ educators may now have more protections in our employment, but our students still lack protections of the most basic kind in their school policies. Check yours: Does it include a nondiscrimination clause on student sexual orientation and gender identity? Now is the time to use our newfound privilege to advocate and lead by example because, even with the Supreme Court ruling, there are political ploys at play to undermine trans youth via Title IX. I say this with resolve and guilt, for I know that I haven’t always been the best example and that I could have done more for many students, but I didn’t because I was afraid. Instead, I did minor things to advocate: I put more LGBTQ affirming texts in the school, counselor’s, and my classroom libraries; provided Safe Zone training and signage for teachers who were interested; encouraged students who asked to bring same-sex dates to dances; made sure to highlight queer writers in the school-approved curricula. It wasn’t until the last few years that I dared to even show my partner in the beginning of the year “About Mr. Whitman & His Class” slideshow. But, I digress. The Southern Poverty Law Center has an enlightening list of ten – often bizarre – myths about LGBTQ persons employed by those who wish to discriminate or do harm to that community. One thing that all teachers need to recognize is that these myths are still believed and used to justify discrimination toward LGBTQ students and educators. Three of them – in my opinion – form the core of what many students experience in their schools in Kansas, and if we’re going to truly support our students, we have to be willing to confront these misconceptions head-on. Myth 1: LGBTQ Persons are Pedophiles or Perverts (SPLC no. 1) This myth often appears when it comes to bathroom and locker room usage – particularly with trans students and educators. While more awareness is finally being afforded to the trans community, many still don’t understand that trans people just want to go to the bathroom, that they aren’t wanting a peep show, that they already feel out of place in their body and want nothing more than to be left alone and to be themselves. LGBTQ youth are one of the highest risk groups for suicide because of so many factors such as rejection from family and homelessness. With LGBTQ students already facing so much stress and pressure, allowing them proper bathroom privileges is the least a community can do to alleviate some of that stress. I personally know the hassle that bathroom usage can bring, as I choose to use the staff unisex bathroom. One homophobic accusation is all it takes to ruin a career. Myth 2: It’s a Sin (SPLC no. 9 & 10) According to the Pew Research Center, 76% of adults in Kansas identify as Christian. As much as we love talking about the separation of church and state, you’d have to be an absolute fool to say that religion plays no part in Kansas’ political or educational landscape. Two respectable professors from state university education programs have told me stories of teachers in training who said that they’d refuse to use a trans student’s pronouns or accommodate LGBTQ students in other ways if it conflicted with their religious beliefs – and they’re not the only ones. For students from all walks of life to have a welcoming climate in a public school, all students must be welcome, loved, and validated, regardless of the staff’s private religious practices. Myth 3: It’s a Choice and/or It’s an Illness, and You Can Change (SPLC no. 9 & 10) I have a hard time deciding which myth is the most damaging, but I’d say it’s a safe bet that telling LGBTQ youth that they’re broken (this ties to the sin myth) and need to change is pretty close to the top of the list. Ex-gay and conversion therapy have done irreparable damage to LGBTQ youth and spread like wildfire in states like ours: my own brother survived it, and I narrowly escaped having to participate. Now that scientific studies and mental health professionals even confirm that trying to change one’s sexual orientation can lead to lasting mental health consequences and even suicide, many states are banning the practice. If we as educators truly value the buzzwords “social-emotional wellness,” then we better damn well do our best to crush this myth for our students. This leads to the inevitable question: What can you as an educator do? That’s easy. Educate yourself. Attend a Safe Zone or Safe Space training. Help start a GSA. Advocate for unisex bathrooms and nondiscrimination policies in student handbooks. Call out anti-LGBTQ comments and microagressions in staff meetings. Watch queer cinema and television. Read queer YA literature. God-forbid, meet and befriend an actual queer person without asking prying, borderline-fetish questions. It’s amazing how human we are. Use your power and privilege to advocate for LGBTQ equality. At the end of the day, I don’t want any student to feel the way that I felt – to be told that they’re hopelessly broken, that God doesn’t love them, that they didn’t pray or try hard enough to change. High school is hard enough as it is. One of my most formative memories originates from high school when I was arguing with my brother – also gay – regarding his sexual orientation. I told him that I wished he was “normal” because deep down inside, at that time, I wished I was “normal.” What I didn’t realize, and what’s taken me close to over a decade to come to understand, is that I truly am that: normal. And all my queer students are, too. And, what a difference it would have made, if just one adult had told me, “You’re fine just the way you are.”  Pictured: Nathan Whitman (left) and Ryan Patrick (right). This photo was grounds for dismissal until Tuesday, June 16, 2020. Pictured: Nathan Whitman (left) and Ryan Patrick (right). This photo was grounds for dismissal until Tuesday, June 16, 2020. About the Author Nathan Whitman is the current Kansas Association of Teachers of English President. He teaches 9-12 English at Burrton High School USD 369 and is also an adjunct professor at Hutchinson Community College. Twitter: @writerwhitman Instagram: @writerwhitman By Erica Shook This year, with all its insanity, was my tenth year of teaching. During those years, I have had a number of LGBTQ+ students pass through my classroom--some who are open with their sexuality or gender identification, and some who don’t choose to share that until after they have graduated high school and have gone on to the next phase of their lives. But all of them hold a special place with me forever. I have had a couple of transgender students over the past couple of years, one in particular whose voice I want to share with you. You see, this student has an amazing talent as a writer and an important perspective to share. I remember how nervous he was the first time the counselor brought him to my classroom to introduce us so that I would know him by his chosen name instead of the birth name listed in PowerSchool. He has a quick wit, a clever mind, and an amazing smile. But he was also struggling, though he shared that with very few people. Early one February, as we were talking about senior showcases, I asked him if he knew what he wanted to do after high school. His answer broke my heart: “I haven’t really thought about it. Most days I’m not sure I’ll be alive that long.” Talking was hard at first, but writing was cathartic for him, so we focused on that as a way for him to communicate his feelings and experiences. Many days we spent my planning period working side-by-side at a table in my classroom: him writing, me grading or lesson planning. I would help edit when he asked. I believe very strongly that what he has to say should be read by everyone--certainly all educators--and I am sharing that voice here with his permission. The following is a small portion of his words, shared with me over a period of months. My hope in sharing with others is that they will reflect on the relationships they have with students in their classrooms or school communities and ask themselves if there are areas in which to grow: “To begin, I struggle with dysphoria from being transgender. Being trans has affected almost every part of my life. Every morning when I wake up, I struggle to get ready to start my day, beginning with chest binding. This can cause many internal problems such as pain and overheating and can worsen already existing problems such as asthma and respiratory infections. It gets hard to look at things positively when every morning you have to face your worst flaws. When brushing my teeth, sometimes I have to refrain from looking into the mirror. If I do, I tend to wonder if I am passing well enough? Is my chest flat enough? Would changing my shirt help? Nevermind, I will just wear a hoodie every day, even when it’s 95 degrees outside. However, that's not even the hardest part. Night routines. That’s the hardest part. After the day is done with its battles, I have my worst one going home and taking a shower. Time to undo the one thing keeping my confidence up. My appearance. There is a mirror, which is very inconvenient when the last thing you want is to literally face yourself. So now my gaze stays fixed. Fixed on one thing. Getting dressed. Do you enjoy a hot shower? I wish I could say yes. That’s where most people relax. Yeah... not me. Truthfully, I do not enjoy a hot shower, or even a cold one. However, I do enjoy the relief of the constant pressure on my ribs and being clean. When I go out to eat, go to school, or go to a public place, I have to use the restroom before I leave the house and normally won't return to a restroom until I get home. Yeah, imagine that discomfort. At school there are two restrooms I am allowed to use: either the one in the nurse's office or the staff restroom. I feel as though this just calls me out further. How am I supposed to feel normal when I can’t even use a restroom 95% of the time? Being trans has caused a lot of mental health issues--it's depressing being separated. Which name do I write on my papers? Which line do I fit in during P.E.? Which locker room do I use? I constantly feel like no one gets it. It is very lonely, and it’s hard to explain why I can’t just go to a certain place, or why I have to cut my trip short because there is no restroom for me to legally use. I constantly struggle with feeling accepted, especially around my family. I have been bullied and harassed for being transgender. I am different--everything is different. I have all the typical teenage bullshit, but on top of all of that, I am trans. I need to find less destructive outlets. To hide one problem, I tend to take on a different problem. I need to find some balance in my feelings. I can never find a good place between being too feminine or too masculine. Puberty is something that is making me anxious; it’s something I am going to have to go through all over again in the future. Throughout life, you have to meet new people. I hate having to introduce myself to anyone. I don’t know how they will feel about me or the intrusive questions they may ask. I don’t know how to explain myself. Really, I don't want to. Coming out can either make you closer to family or destroy your relationship with them. There are countless reasons why relationships are difficult with a significant other. You have to open up even when you don't want to (about your triggers, about where they can and can’t hold you, about things they can and cannot say, and about dealing with how their family and the public feels about you). It feels so unfair to put someone you care about through all of that. I hate name problems, like when I am dead named (called my birth name) because of my family in front of someone who knows me as my chosen name or having to explain pronouns. My future is my biggest worry, aside from my day-to-day problems. I don’t want to go to college, and that is going to upset my family. I have fear of what my future might look like. Financially, for myself, things are going to be very expensive. Things like surgeries and testosterone. I fear failure. I hope to one day do something big, like write a book, or maybe even a play. I want to try and make a difference for kids like myself. But, I worry about being fired due to my identity, being harassed or bullied by the public or coworkers, potentially ending up homeless, being denied housing or evicted, denied medical care or being targeted by others. A lot has been taken from me because I am Trans. My childhood was not always happy, and I remember being alone a lot of the time. My sister and cousins never wanted to play things that I enjoyed. They played with makeup or Barbies and did each other's hair. They would play house, and I would only take part if I had a male role...like a dad or brother. I didn’t enjoy having family occasions--my birth name was said and used too often. I love the beach. God I love it. The sand, the water and the smell. It helps me feel free. It helps my mind. Which is amazing but sad because I have to wear a t-shirt. It’s hot there, and it makes me uncomfortable. The city pool is just Hell. I can’t get married wherever I please. I can’t have my own kids like a normal cisgendered male, and that kills me inside. Thinking about it makes me sick...it makes me feel empty. I think I hate that part the most. Anger overwhelms me, and makes me hate the world as well as myself. I hate my body so so deeply. I love children, but having them, that is going to be hard. It’s unfair for my significant other. I fear I am not enough, or won't be enough. I feel that I am not enough. I am not as strong nor as big as a typical male. I don’t have many friends because it’s hard to bond. I never got to play the sports I wish I could have or write the name I felt was right on the top of my papers. I never got to express myself. I fell... deep. Into a hole of self-loathing and doubt. Sleep sucks, waking up sucks, peeing sucks, going out to eat sucks. I am alive, but am I living? I am scared. I am so scared of losing hope and just not having anything but myself. I was always alone, so I came out to fix that. I was wrong because now I feel even more alone. It is hard to even breathe thinking of all the things I didn’t get to see. I didn’t get to control. Yet, I am still in the same spot and not shit has changed. The world has expressed my unwelcomeness, but I did not ask to be here. When I am asked why I chose this, I say I didn't choose a thing. I didn’t choose to hate my physical existence. I didn’t choose to fight all the time with loved ones or my own personal battles. I did not choose to struggle every day. I wish that was understood. I want nothing more than what those people who question me have. I want what you do, I promise. I have yet to understand why such bad things happen to the best of people. Especially things that no one should ever go through. I guess life just isn’t fair. I feel sad right now, maybe the word I'm actually looking for is overwhelmed. I broke yesterday. I cried...on the floor in the bathroom and made some very bad decisions. I just hurt...all too bad. Replacing emotional pain with physical pain. Does it help? Well, my honest answer is yes. But only for a moment. Only while it's literally tearing you apart. Then its effects last forever. In a helpless spiral you will fall. I want to love and be loved. I want to spread it and I want to feel it. I want to love myself the most. It is so confusing. I hate my physical being; however internally, I don’t believe I am terrible... I hope one day it all won’t hurt so bad. Some things that happened, I will take to my grave remaining secret. That is where they belong. Dead. As dead as they made me feel. In time I will be better. I hold onto that thought. I don’t know how, or even when. But that time will come.”  About the Author Erica Shook is the English Department Chair at McPherson High School, USD 418. Because of her passion for students, educators and education, ELA, YA literature, and social activism, she is also a Project LIT Community chapter leader and the KATE Vice-President. One of the most important things she has learned during her time teaching is that absolutely everything that happens in one's classroom hinges on the relationships built there. Representation matters and is an essential component of those relationships. Follow her on Twitter at @Ms_Shook or on Instagram at @ms_shook for book suggestions to build classroom libraries or for continued professional development. You can also check out https://www.glsen.org/ or https://www.tolerance.org/ for additional resources. By Madison Loomis I have a question that keeps repeating in my head over and over and over again: Am I going to remember how to be a teacher? My head chimes in with the same response - Duh, yes you will - it’s like riding a bike. Isn’t it? Or is it? Will I remember how to set my expectations the first day, or will I freeze up at the front of the room like I did the first time a lesson went wrong? I haven't had face-to- face interaction with my students in SO LONG, and now the official school year is over, which also concludes my first year of teaching. Yes, I am a baby teacher who not only survived her first year, but survived amidst a global pandemic. This year of teaching really paralleled a classic coming of age story, but for someone who transitioned from novice teacher to experienced professional . This transition was full of classic, cringeworthy moments. However, while reflecting on these moments I’ve realized that they were necessary. They helped me to grow, and with this growth came comfortability, and most importantly, confidence. Reflecting back on this year, my confidence only came through conquering some of the weirdest situations I’ve ever experienced - you know, like turning around to a pair of tidy whities that magically appeared on a desk in the middle of reading The Hunger Games... or that time when someone played inappropriate noises from a hidden Bluetooth speaker in my room that ignited a frenzy to find where they were coming from... I remember walking out of my room sometimes and looking at my coworkers like, "what the heck just happened last block?" I really thought I had seen (and heard) enough for my first year. I locked my door on March 12th feeling pretty good. Feeling like I might be getting the hang of this whole teaching thing. But then everything got way more serious. I left that Thursday before spring break to go to the store after school. I was out of toilet paper at the worst time, only to see people rushing and scared in every aisle. I think that's when it dawned on me that things weren't okay. Little did I know, the world I knew would not exist anymore. Teaching should be like riding a bike, right? You might be a little scared after not riding for a while, but you’re reassured after the first 5 seconds back on the bike, that you got this. You’ve practiced, and you’ve fallen down A LOT, but each time you get back up, things feel a little easier. I was finally ready to ditch my teacher training wheels in the fourth quarter upon my return. But during spring break, someone let the air out of my tires. My wheels weren’t turning anymore. Literally. I froze when the governor announced we would not be returning to school as we knew it. My brain went radio silent. I realized I would be switching from the comfort of riding a bike to climbing on top of a contraption no one had ever used before - one still being built. Flash forward a few weeks. With the indefinite school closures, l was given 15 minutes to get my stuff from the building. 15 minutes. My room didn’t even feel the same - it looked and felt like a ghost town. I locked my door this time, unsure when I would see my classroom again. The news became constant background buzzing as life changed every day. My heart broke when I thought of how each one of my 160 students’ lives were changing too. I am thankful for every phone, text, Google Classroom, email conversation that I was privileged to have with them, It was horrible to not be able to say “good bye” to them, but I hope that I will be reunited with their faces soon. Before this, I had the belief that teaching gradually became more normal with every day . Things start awkward, even scary, and then, somehow, teachers grow and find their voice. Before COVID-19, I believed that once you found your voice, you were set for life. Unfortunately, teaching is much more dynamic than that. It throws us curve balls all the time. And it takes a special human to adapt and adjust when the definition of normal changes year by year, hour by hour. It takes a special human to care so much about their coworkers and every student they teach - to find every possible way to solve every single problem. And educators are exactly that - special. I cannot tell you how many times I have heard the word, “relationships” since I started teaching. Relationships with students help us break through obstacles in their behavior and learning; they are how we establish a positive classroom environment. We will always have the memories of our high school teachers that told us we were special, the college professors that challenged us, the mentor teachers who never gave up on us, and the friend down the hall whose room became a safe haven of help during our plan time. But relationship building shouldn’t stop once we step foot outside our classroom. As an educator, you are part of a community of some of the coolest people on the planet (maybe I’m just biased). My colleagues at Southeast each bring their own voice, talent, and experience. They’ve shared numerous ideas and lessons; advice and comfort. One of them even bought me fuses for the string lights in my room. Another helped me compose a write-up regarding the inappropriate noises from the hidden speaker incident. If they hadn’t, I might still be trying to put that incident into words to this day. They were incredibly vital as education moved into uncharted territory this final quarter. I am thankful that I was able to ask them thousands of questions a day, and they still helped solve them even though they were struggling themselves. And truly, I think that’s all that really matters - whatever happens to us educators, weird or normal, there will always be someone there to support us. I can’t tell you how proud I am to be an educator amongst so many resilient, strong, caring humans. Our own lives changed completely, yet we still care about everyone else. Our jobs are centered around human interaction, and we have the power to make an impact, socially -distanced or not. The future is still unknown for all of us right now. Whether we have a year of experience or years of experience, none of us know what we will be returning to next year. But I do know this - we will continue to help those around us, regardless if it is through an instant message, a text, or a meme. We will adapt, and we will change together. The relationships we build with our colleagues will turn into lifelong friendships, and nothing is going to change that. I am not the teacher I was in August, and I will not be returning as the teacher I was before spring break. So reflecting on that question I asked at the beginning, “Am I going to remember how to be a teacher?”, I’ll tell you what I know for sure: I am going to remember how the kids I taught this year made me feel. I am going to remember how to laugh. I am going to be resilient in the face of change. And most importantly, I’ll remember that I’m going to have one heck of a support system by my side at all times. So thank you to educators, new and old - we are confused and frustrated with our future. But always remember that you are appreciated. Thank you for believing in me, so that I can believe in my students.  About the Author My name is Madison Loomis, and I have just completed my first year teaching ELA at Wichita Southeast High School. I graduated from Wichita State University in 2019. I love concerts, my grumpy cat Gracie, and I LOVE reading young adult literature. You can find me on Goodreads or reach me at msloomis@usd259.net By Dr. Katie Cramer As a teacher educator, I have been preparing future middle and high school English teachers—first in Georgia and now in Kansas—for more than a decade. Since 2007, I have used position statements from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) to support my professional practice, particularly my decision to center sexual and gender diversity in my curriculum. When NCTE passed the Resolution on Strengthening Teacher Knowledge of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Issues in 2007, I was able to further defend my curricular inclusion of sexual and gender diversity in my English methods class against resistance from a small but vocal minority of my teacher candidates who argued that …

Aside from expressing my dismay at each of these claims (and my absolute horror at the last one)—as well as my relief that I’ve not heard teacher candidates express these views in the past 10 years—I will not belabor them. In fact, I have written about these challenges before, including in Kansas English (Mason & Harrell, 2012) and more recently in a chapter in Incorporating LGBTQ+ Identities in K-12 Curriculum and Policy (Cramer, 2020). Instead, in this piece, I want to remind all of us that we can be even more powerful in our teaching for social justice when we seek out support from our professional organizations at the state and national levels. What are position statements? For the past 50 years, NCTE has published position statements on a number of issues that guide and support our professional practice. According to NCTE, position statements “bring the latest thinking and research together to help define best practices, offer guidance for navigating challenges, and provide an expert voice to back up the thoughtful decisions teachers must make each day” (NCTE Position Statements). They begin as resolutions, crafted and submitted by a group of at least five NCTE members and reviewed by the NCTE Committee on Resolutions before being discussed and voted on at the Annual Convention and later ratified by NCTE membership. NCTE notes the value of both the process and the product on its resolutions page: “When a resolution is ratified it signals to members and the wider education community that these issues are top concerns. Most resolutions also come with research about and suggested solutions to the problem. As such, a resolution is a tool you can use as an educator to advocate for these issues, knowing you have the backing of a national organization in your stance.” (NCTE Resolutions) The oldest position statements NCTE lists on its website were discussed and voted on at the NCTE Annual Business Meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1970 and include fascinating and still relevant resolutions on …

More recently, NCTE membership has ratified statements that center sexual and gender diversity. During LGBTQ Pride Month, let’s turn our attention to two position statements that support our efforts to recognize and affirm sexual and gender diversity in our schools and curriculums. Resolution on Strengthening Teacher Knowledge of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Issues (2007) NCTE’s Resolution on Strengthening Teacher Knowledge of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Issues was ratified in November 2007 at the beginning of my career in teacher education, and it has provided the support I needed to center sexual and gender diversity in my teacher preparation curriculum. It states that “effective teacher preparation programs help teachers understand and meet their professional responsibilities, even when their personal beliefs seem in conflict with concepts of social justice” (NCTE, 2007). It advocates for the inclusion of LGBTQ+ studies in teacher education programs, even going so far as to advocate that accrediting bodies recognize the importance of the study of LGBTQ+ issues in such programs. This resolution/position statement not only strengthened individual faculty members’ rationales for the inclusion of sexual and gender diversity in their coursework, it also led to positive changes within the NCTE. Less than two years later in March 2009, English Journal published its first themed issue on sexual and gender diversity, and more recently, the NCTE formed the LGBTQ Advisory Committee on which I am currently serving my second term. Statement on Gender and Language (2018) In 2018, NCTE members ratified the Statement on Gender and Language, which evolved out of NCTE’s previous position statements on gender and language from 1978, 1985, and 2002. The most current iteration of this statement “builds on contemporary understandings of gender that include identities and expressions beyond a woman/man binary” (NCTE, 2018). This 12-page document—one of the longest NCTE position statements I’ve encountered—features a plethora of information to guide teachers’ understanding of gender diversity. It defines gender-expansive terminology; describes research-based recommendations for working with students, colleagues, and the broader professional community; and includes an annotated bibliography of resources to help us “use language to reflect the reality of gender diversity and support gender diverse students” (NCTE, 2018). Stay Tuned … This summer, I was invited by the NCTE Presidential Team to collaborate with colleagues across the U.S. to revise three statements on gender and gender diversity. Two of the statements are 25 and 30 years old, respectively, and they need considerable updating as conceptions of gender and sexuality—and the language we use to describe them—have evolved (and continue to evolve). This committee, under the leadership of Dr. Mollie Blackburn, is currently planning to address both sexual and gender diversity in curriculum design in our revisions, and we hope to have one or more statements ready for discussion and vote at the 2020 NCTE Convention, which will take place virtually this year. Your Next Steps I invite you to take some time this summer, as you reflect on your curriculum design and prepare for the next academic year, to engage in the following activities:

Alongside our state affiliate the Kansas Association of Teachers of English (KATE), NCTE’s vision is to empower English language arts teachers at all levels to “advance access, power, agency, affiliation, and impact for all learners” (NCTE About Us). NCTE’s position statements are just one of the many ways the organization enacts that vision. References Cramer, K.M. (2020). Addressing sexual and gender diversity in an English education teacher preparation program. In A. Sanders, L. Isbell & K. Dixon (Eds.), Incorporating LGBTQ+ identities in K-12 curriculum and policy (pp. 66-111). IGI Global. Mason, K. & Harrell, C. (2012). Searching for common ground: Two teachers discuss their support for and concerns about the inclusion of LGBTQ issues in English methods courses.” Kansas English, 95(1), 22-36. NCTE (n.d.). About us. https://ncte.org/about/ NCTE. (n.d.). Position statements. https://ncte.org/resources/position-statements/ NCTE. (n.d.). Resolutions. https://ncte.org/resources/position-statements/resolutions/ NCTE. (2007, November 30). Resolution on strengthening teacher knowledge of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) issues. https://ncte.org/statement/teacherknowledgelgbt/ NCTE. (2018, October 25). Statement on gender and language. https://ncte.org/statement/genderfairuseoflang/  About the Author Katherine Mason Cramer is a former middle school English teacher and a professor of English Education at Wichita State University. She has been a KATE member since 2010 and an NCTE member since 2000. She serves on the KATE Executive Board, and has served as Editor of Kansas English since 2017. She can be reached at Katie.Cramer@wichita.edu. By the Andover Central ELA Department  The Andover Central ELA Department - Back Row, L - R: Patrick Kennedy, Derek Tuttle, Mark Fleske - Front Row, L - R: Deborah Eades, Adrienne Stenholm, Briana Riddle, Allison Craig The Andover Central ELA Department - Back Row, L - R: Patrick Kennedy, Derek Tuttle, Mark Fleske - Front Row, L - R: Deborah Eades, Adrienne Stenholm, Briana Riddle, Allison Craig Patrick Kennedy would not want this blog post published. It would make him feel proud, but it might also make him a little uncomfortable. You see, Patrick Kennedy never set out to focus attention on himself. Instead, he focused attention on students and co-workers in a fun, profound, and unforgettable way, leaving a deep rooted and everlasting legacy. Patrick Kennedy died unexpectedly April 29, 2020. When we think of great English teachers to acknowledge during Teacher Appreciation Month, we would be remiss not to remember him. So, as his friends and department members, we share these words to honor his legacy. If you were to ask a co-worker or student about Mr. Kennedy, the initial answer might have something to do with his impressive collection of Converse shoes and matching shirts. It might have something to do with his ever expanding baseball hat collection or his messy desk. Inevitably, however, someone will mention Shout Out. Shout Out is just one of Mr. Kennedy’s legacies. It’s a little weekly show he developed and produced to highlight the accomplishments of students and staff. Every week, on his own time and with his own resources, he would gather a few students to “shout out” to teachers who had impacted them in positive ways, showcase students’ accomplishments, and create awareness of cool things happening at school. Each episode is filled with some kind of crazy antic: Mr. Kennedy dressed as a giant turkey for Thanksgiving,or a Star Wars character, or a pirate. While he created entertaining and innovative shows, the students were always the focus. He ended every show the same way, with a big, “I’m proud of you!” However, Shout Out is only a small sliver of what Mr. Kennedy left behind. We’ve all heard the saying that while people will forget what you said and forget what you did, they will never forget how you made them feel. How Mr. Kennedy made people feel is his real legacy. He had this intuitive nature of creating intimate connections. Though he was one of the most interesting people you could ever know, those connections weren’t about him. His interest was in you, in forming more than a friendship. It was more like a heart tether. With one dry-wit comment or hilarious deadpan expression, he could remind you of a dozen conversations you’d shared that you always came out of feeling better than when you went in. He had a knack for creating private jokes and in-depth conversations that lasted years, literally. With one colleague, he continued a habitual discussion of his extensive movie collection. With another he shared an ongoing love of literary puns, and with another, Star Wars quotes and sports highlights. For our department, he challenged us through example to raise the bar on our own work ethic, school involvement, instruction, and humility. Mr. Kennedy built close, friendly, caring connections with many students from the present and the past. No current or former student could walk by him in the hall between classes without the two of them exchanging some word or nonverbal cue, sometimes as a tradition established many months or even years prior. One particular student played rock-paper-scissors with Mr. Kennedy every single day on his way to another class. Because he had taught the young man in middle school and high school, who knows how long ago they established that tradition? This senior looked forward every day to the banter and competition of the simple game--and the connection to his former teacher. It was a daily reminder of a heart tether that transcended classroom walls. Mr. Kennedy was more than just a colleague; he was also a devout friend who socialized in many different groups. He would take trips with family or high school and college buddies to see as many baseball stadiums as he could, hoping to visit all fifty states eventually. He shared countless stories about wedding trips with friends. He would meet with former colleagues routinely to stay caught up, and he was always there to lend a supportive ear or give advice when asked to do so. Besides his love and care for people, Mr. Kennedy also had a love and care for the subject he taught. His love of the written word was not only contagious, it was also inspiring. He gushed over the Romantics and Whitman’s Leaves of Grass to the point where some of us started thinking maybe we’d missed something in our study of them. His students, even the reluctant readers, analyzed Gatsby in ways that would make even Fitzgerald take notice. When students graduated from his classes, they knew--really knew--clauses and phrases and poetic devices. They learned it because they understood that he expected them to. Mostly, though, they learned it because he made it accessible, interesting, and powerful.Their continued interest in stories carries on his legacy. The kids he coached looked to him for lessons in character as much as skill. His basketball boys knew the value of hard work and tenacity because he lived the message. They might miss the shot, but they would never miss the opportunity to learn the lesson. Nate Brightup, one of his Scholar’s Bowl students explained it this way, “Mr. Kennedy was someone who helped to center the team. It was like he could set us into the zone. If we thought we were hot stuff, he would remind us of our mistakes, not as a way to bring us down, but as a way to remember that there is always something to improve. The team shouldn't ever become complacent or comfortable with where we were at, we should keep on working.” Kate Calteaux studied with Mr. Kennedy in middle school. Her experience clarifies his inspiring nature. “For him to create an environment for me when I was thirteen or fourteen years old to understand the magic of English meant everything to me. It was a place where I could go and be a nerd and cut loose because I knew he wouldn’t mind. In fact, he would encourage that. He cared about every single student. No matter who you were, he was going to stick up for you, encourage you, and support you. And now, for me to want to become an English teacher, I owe a portion of that to him. He taught me that words and grammar are so much more than a subject. He made learning so exciting. He wouldn't want us to be sad. At the end of the day, he would say, ‘The show must go on.’” Mr. Kennedy is the kind of person whose presence made such a difference that his absence will make an even bigger one, but the heart tether remains strong, ensuring a continuance of inspiration. As we celebrate and remember him, we understand that, in fact, we are his legacy: his students who take with them into the world a love of language and a connection of caring and his co-workers who will attempt to fill the gap his absence leaves in our school community. As students figure out a way to carry on his Shout Out and create shoe drives in honor of his Converse obsession, and spread hashtags of his catchphrases through social media, we all know our show must go on. When someone pours into you like Mr. Kennedy has, we have the privilege and obligation to continue the legacy so that when he looks down on us, we know he’ll smile, raise a finger to the air and shout out, “I’m proud of you.” If you have a memory of Mr. Patrick Kennedy or any teacher whose legacy you have the privilege and obligation to continue, please add it to the comments, so we can continue to be inspired. About the Authors

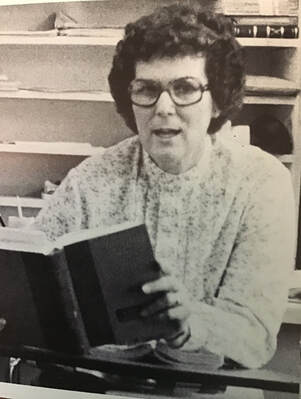

The 2018 - 2020 Andover Central High School ELA department exemplifies teamwork. Though we were only fully together for two years, we enjoyed a camaraderie that can be rare in workplaces. We each had our specialty and our special interests, but it was our sincere respect for each other that held this team together. Sometimes, a person is blessed to be in the right place at the right time with the right people. That's what we had for two years. Going forward, it won't be exactly the same, but the fact is now that we've experienced it, we won't settle for less. By Dr. Elizabeth Minerva  Sara Lamar, my favorite high school teacher. Sara Lamar, my favorite high school teacher. My favorite English teacher kept a loaded water gun handy in case a student drifted off during her AP English class. She once removed a spoke-like film reel from its case, tiptoed across the room, and dropped the empty metal canister on the hard floor beside a sleeping student’s desk. We were all delighted, save the startled sleeper. She could be terrifying when she asked a question about one of our assigned books, such as Absalom, Absalom (Faulkner was her favorite). Her bright blue eyes would rove from face to face until she snagged someone. She expected a lot and would push for more if she saw a student verging on a significant realization. In no other class did I think or write as intently as I did during her in-class essays, and this was before I discovered caffeine. Her timed tests were a pure adrenal joy. Sara Lamar was my favorite high school teacher. She knew so much about the literature we read that she made each book seem essential to understanding humanity: James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness/Secret Sharer, Mark Twain’s The Mysterious Stranger, William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Each new book was a revelation. She appreciated students’ ingenious ideas in class, guided us when we went off track, and encouraged our individual interpretations. I didn’t talk in class unless called upon. When she did call on me, it was because I was caught in her tractor beam gaze. One morning, Ms. Lamar gave the class a brief task and asked me to talk with her in the hallway. She had noticed that I’d seemed upset all week and wanted to know what was wrong. Voice shaking, I told her that my two-year crush had asked one of my best friends to the prom, which I learned when I called to ask if he wanted to go with me. This travesty led -- a few days later-- to the Latin teacher ordering me and the friend into the hall to deal with whatever was causing our furious note-passing. In the cell phone age, we would have spent the class period jamming our thumbs into our screens; then, our friends passed the folded up sheets of notebook paper hand to hand, all of them in on the conflict. This is a story I tell high school students with some self-deprecating humor (so much angsty material!), but at the time that boy mattered more than anything. Although teachers usually liked me -- quiet, conscientious, a copious taker of notes -- Ms. Lamar was the one who let me know that she saw me. We talked for a few minutes in the hallway. I cried; she listened and offered sympathy. It won’t always be like this, she assured me. When class resumed, I felt better -- not about the boy, but about being heard. My high school years occurred in a very different time. If a student knocked at the door of the teachers’ lounge, a resentful adult would appear in a slice of doorway, puffs of cigarette smoke wafting into the hall. “What is it?” the teacher would say tersely. On the south side of the school, there was a sloping student parking area where you couldn’t see inside the cars through the interior fog (“Freak Hill,” it was called). Freebird… Black and white students played on teams and served in student government together, but interracial dating was rare. Gay students, what? My American History teacher, a middle-aged woman with a perfect, shoulder-length flip, picked fights with our textbook’s prejudicial treatment of the south. Did she actually use the term “war of northern aggression”? Seniors had to pass a one-semester Americanism v. Communism class to graduate (no Bolsheviks in our bathrooms, thank you). I sat near the same people all four years in college prep track classes because alphabetical order was the obvious choice. Robin Montgomery, who often sat in front of or behind me depending on the class, maintained a 25-inch Levi waist size all four years. Although most administrators and teachers at Tallahassee’s Leon High School were kind, intelligent, and devoted, trauma-informed teaching would not have taken root in that red clay soil. If the houses on dirt roads that branched off Henderson Road really did not have central air and heating or other utilities, well, that’s just the way it was. Some people are poor. When baccalaureate was canceled my senior year due to complaints about holding a religious ceremony on school property, a civil war of words erupted; the church/state divide might’ve been legal but it wasn’t tradition. The school’s service clubs -- Key, Anchor, etc -- operated like fraternities and sororities with legacy members; many students who went on to public office started off in those exclusive groups. Life isn’t fair, is it? Deal with it, and hold your head high. We were a pride of lions. My high school was about the size of the one where I now teach in Wichita. My students don’t sit alphabetically in rows of desks, nor do the students in most of the ELA classrooms nearby. While ELA teachers still teach dead white male writers, the offerings are far more diverse these days. In addition, teachers are trained to know what ACES are and how they impact student performance, to recognize suicide warnings, to practice trauma-informed responses to student behavior. Individual relationships with students are essential because, without these connections, we can miss a key aspect of a student’s motivation. If you teach the material but don’t reach the students, what was accomplished? We are in this together and we care about our school community. Pride, Respect, Excellence. We are a sleuth of Grizzlies. When Ms. Lamar called me into the hallway that day, I already knew that she cared about me as a student. We had talked about my college choices. I’d stayed after class, questioning her about comments on my papers. She had supported me when I dropped typing to take Southern Lit with her senior year (the typing teacher was apoplectic -- a girl should have secretarial skills! What if I had children and my husband died and I had to support my family? I would need that second semester of typing). After my freshman year of college, I went back to see Ms. Lamar and she was eager to hear how I liked college, how my English professor had interpreted Faulkner. She had been sure I would enjoy college more than high school, and she was right. What I can take from all this as a teacher is obvious. Any teacher reading this knows how much those moments of recognition mean when a teenager just needs someone to look beyond the curriculum and see their face. My appreciation of Ms. Lamar is a call to be compassionate when students are struggling with life circumstances. Many of my students have far more challenging personal issues than a prom date. Students face serious mental health concerns, either their own or within their families. They might work a ridiculous number of hours at a low-paying job, watch younger siblings, bounce between households without a sense of stability, witness or participate in dangerous, risky behaviors. Schoolwork can be a lost concern when basic needs such as shelter and safety take precedence. Too, a boy or a girl who broke your heart is still cause for distress, as is the disappointing grade, the lunch spent alone in the Commons, the new glasses that no one noticed, the crap day that just keeps going. A moment of kind concern isn’t reserved for traumatic instances. And now, throw in a pandemic. During the COVID-19 crisis, reaching out to students has lacked the face-to-face barometer, the reward of seeing a teen smile or relax when they realize you just want to know how they are. In a professional learning session, a colleague suggested using Remind for short check-ins with students of concern, and I’ve found that to be a simple way to say “hey, how are you? Heard you’re working a lot of hours these days” or in some way let them know they are on my mind. Even students who do not end up turning in work will respond to a short personal inquiry. This isn’t, after all, about the student’s grade. So, I don’t wield a water gun or teach Faulkner, but I do still rely on the example Ms. Sara Lamar set. I see you. You matter to me. Are you okay?  About the Author Lizanne Minerva is an ELA teacher at Northwest High School in Wichita, KS. A native of North Florida, she is a Florida State University graduate. By Angie Powers  Examples of Mrs. Bushman's "plus" feedback. Examples of Mrs. Bushman's "plus" feedback. My grandmother was hard and sturdy. She taught me that being a woman, a human even, meant “sucking it up.” Life doesn’t care so much about your feelings; it will simply go on. She knew, with great certainty, that her job was to raise me as a strong woman. Enter Kay Bushman Haas. I knew, without really knowing, that Mrs. Bushman was a great teacher within moments of walking into her class as an introverted freshman. I didn’t know the accolades she had earned; I just knew that teaching came out of her pores. She effused her passion for language at the beginning of every class with our Daily Oral Language work--not something she mindlessly pulled from a book, oh no! She crafted our language workouts from student writing. She made nouns and verbs and adjectives and adverbs titalating. She invited us into Verona, Italy; Tuscumbia, Alabama; and even London, Oceania. I immersed myself in their pages, emerging after the last somehow expanded. I walked into her classroom knowing I wanted to be a teacher; I walked out knowing I wanted to be an English/Language Arts teacher like her. Lucky for me, Mrs. Bushman taught me again in Creative Writing sophomore year. I had been hoarding poems for years, so this was a class I desperately wanted to take. But, like most budding writers, I was terrified of sharing my writing. There was no way I was going to take that risk... well, until I learned she was the teacher. She taught me that my writing doesn’t have to be “good” or “bad,” but that writing is about those moments. Those punch-you-in-the-gut, jump-off-the-page moments. They can be fleeting, even buried. She shared those moments out of our writing anonymously in front of the class, finding the pearls in the mollusks of teenage angst, lonely sci-fi, and saccharine romance. I would sit--really perch--on the edge of my plastic seat, waiting to see if one of my moments would come out of her mouth. Sometimes, they did; sometimes, they didn’t. But that didn’t really matter because once she handed me my pages, they would be cluttered with plus signs, signifying that she saw every moment I offered. I would spend hours re-reading every moment she marked, trying to figure out what made that moment--or even me--worthy. I knew Mrs. Bushman was a strong woman. She was like my grandmother in that sense. They both weren’t tongue-holders; some might have even called them pushy, or worse. They both walked with a confidence that lacked arrogance to the discerning eye. So imagine my surprise when Mrs. Bushman smashed my grandmother’s definition of strength before my very eyes.  Kay and Angie at the Kansas Teacher of the Year banquet. Kay and Angie at the Kansas Teacher of the Year banquet. We spent a lot of time in Creative Writing journaling. I looked forward to the quiet time to write, finding asylum from the din of adolescence in the silence. I can’t remember if Mrs. Bushman shared her poem after one of our daily journaling sessions--or if it was something she shared at another time--but I remember her sharing. The poem was about loss. As she read, I constructed plus signs in my head for each of her moments. I was in awe that she shared so fiercely, reading her own words in front of a group of people--albeit a motley crew of drama-prone teens. And then it happened. Her voice cracked. I looked around, uncomfortable to stare directly at raw emotion. She wiped tears from her face. And then we continued class. Nobody knew that she had just incinerated my idea of strength. Over 25 years later, the yin and yang of strength and vulnerability still give me pause. I am more practiced at my grandmother’s strength: it carried me through long days as a teen mom and long nights of studying. It helped me through my first year of teaching while pregnant, strangely enough in the same teaching position that Mrs. Bushman left the year before. That kind of strength was about risk aversion: put your nose down, work hard, and never EVER let them see you sweat. But the vulnerable strength of Mrs. Bushman is the polar opposite of my grandmother’s and all about risk-taking. Like writing this. Those of us teaching today have the same power as Mrs. Bushman, who I now call my dear friend, Kay. Whether we teach from a classroom or a cart or our own homes, our lessons may begin with standards but they don’t end there. Our students learn a lot from us--not only from what we say but what we choose to not say. Kay had the strength to show her vulnerability. She took a risk, not knowing the impact on me--or my classmates. Her tears revealed her hurt; the crack of her voice told me that she knew she was going to be okay. Isn’t that what our students need to know right now? We all may hurt in different ways, but we can be okay. Social-emotional learning and resilience are hot topics in education, but master teachers of the past have grappled with them for centuries. Today, our challenge is to meet students’ needs in these areas during a time of uncertainty and amplified inequity. The weight of this challenge, no doubt, will require both my grandmother’s and Mrs. Bushman’s strengths. I’m putting my nose down, embracing my grandmother’s grit, by studying what it means to be an “emotion scientist” with Permission to Feel by Marc Brackett, Ph.D. However, I’m also living the truth of vulnerability. I can’t count the number of times I’ve felt the annoying sting of tears in my eyes for all of the things I’m missing at the end of my tumultuous twentieth year of teaching: my students, my colleagues, my family. Sometimes I’m angry. I’m furious that some of my students are ashamed of being who they are because of the anti-Asian sentiment COVID-19, and some of our nation’s leaders, have stoked. I resent the fact that some of my students need food, internet, or even a hug, and I cannot provide them all. But instead of feeling all of these things alone in my house, I choose to share them--even though you can’t hear the crack in my voice. I choose to share them because of a teacher--now friend--named Kay. And I know that, in the end, we can be okay.  About the Author Angie Powers is the mother of two strong humans. She's finishing her 20th year of teaching from her kitchen table in Olathe, KS. Her passion for advocacy has provided her many professional opportunities: NEA Board of Directors, Welcoming Schools facilitator, 2018 KTOY Team, Greater Kansas City Writing Project Fellowship, and National Board Certification. You can follow her on Twitter at @angsuperpowers By Amanda Little  Robert Frost is quoted as saying “Poetry is when an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found its words.” It is cryptic quotations like this one that often make people run from poetry screaming. While I identify with Frost’s quip as an amateur poet and an aesthete myself (full confession, I had to look that word up), I can understand why poetry has a tendency to scare off students and teachers alike. One of my main goals, however, is to bring a love of poetry back to my students. Or at least make it so they don’t groan in anguish any time someone utters the word. I have used various methods in the classroom to try and make poetry more accessible for my students. Aside from reading a poem a day out of the critically acclaimed Poetry 180: A Turning Back to Poetry, I try to disarm the word daily. When I start talking about poetry in depth, which is usually sometime around National Poetry Month, I often hear one of two things: “Really?! Ugh!” or crickets chirping louder than those found on a pastoral night in one of our beloved Kansas prairies. But I then ask my students if they enjoy music. Usually, most hands go up or heads nod in assent. Then I drop the bomb. Music. is. poetry. (Wait, whaaah???) I remind my juniors of our Native American Literature unit, of the fact that the oral traditions of most cultures were often first sung around a fire, set to a rhythm to bring it to life and to help them remember their sacred legends. I explain to them that the iambic foot is so widely used in poetry because it mimics our own heartbeats. duh-DUM, duh-DUM, duh-DUM. Poetry is a part of our very being and body. I assure them that most poets aren’t trying to hide a “special” or “deeper” meaning in the words of their poems. That readers connect with some poems and poets more than others. That to a certain degree, a reader gets to connect with each poem in their own unique way. And I comfort them with the knowledge that all a poem is is an astute observation about a microscopic slice of life. Finally, after we’ve taken the fear out of poetry, I introduce them to poet Taylor Mali’s poetry game: Metaphor Dice. Because many teenagers either lack the words or the experiences to put life into lyrics (well, most of us adults do, too, for that matter), Mali, former-teacher/SLAM poet/advocate himself, invented a game to help us identify and connect words with life. He has a starter set and the new “Erudite Expansion” pack. I stumbled across these as I was fan-girling and stalking Mali’s Facebook page—Mali has been a favorite of mine since discovering him in college. (And I continue to follow him. #Noregrets!) You might know Mali for his poem “What Teachers Make” found in his collection, What Learning Leaves. I usually use Mali’s dice as a brain-storming activity for our summative poetry project in which the students must create their own “book” of poetry (usually between 6 and 9 poems depending on the time we have). I give them choices, examples, and mini assignments to help them build different styles of poetry like haiku, concrete poems, acrostic theme poems, and traditional forms (like sonnets). I also let them explore mimic poetry, using an excerpt of Whitman’s “Song of Myself” as the mentor text. I’ve even let them explore slam poetry after viewing a student edition of SlamNation (a 1998 documentary by Paul Devlin). They have quite a bit of freedom balanced with guidance to choose forms and create the poems that will express themselves best. My goal is to help them find their own way to voice their own experiences. And this is where Mali’s dice come in. The way the dice work is simple. In the original edition, there are 12 dice, 4 red (subjects), 4 white (adjectives), and 4 blue (objects). When you roll the dice, you see which subject, adjective, and object make a metaphor that you can identify with. Sometimes you get remarkably insightful ones: Home is a burning kiss. Other times you get hilarious ones: Your mother is a desperate party clown. And still other times you can mix it up by using negation: The world will never be a bright trophy. Once you have found the metaphor that strikes you through your heart, you know you have a poem started. Then the work becomes putting into words why that metaphor is true. Here’s a finished product of my own: Fronts of the Mind Regret is an obstinate odyssey relentlessly pursuing the pursuer memories attacking blindly-- a cyclops, wounded, livid, afraid (but hind-sight is only 20/20 if the view remains unskewed) escape only possible for those with the tools the wherewithal the means still forfeiting friends in the chimerical front that is the mind labyrinthine, snare-filled busy Regret is the perilous sojourn we choose for ourselves knowing we eventually come to the fork in the road realizing we must take the path of self-clemency (the path less traveled) for the sake of our own survival for the sake of survival the sake of sanity the journey of regret must cease and only we choose that for ourselves If you didn’t notice it, my starting metaphor was regret, obstinate, and odyssey. I related to that in my own thought patterns and redemption to create my poem. Many of my own students, especially the ones who thought they hated poetry, have found the days that they played with Mali’s dice to be some of the most fun of the year—I have survey answers to prove it! I have limited sets, so my students work in groups, passing the divided sets from one group to another throughout the class time, which only adds to the conversations and fun. I also pair the dice with Rory Story Cubes to help students brainstorm ideas for their own poetry projects. This year, I am heartbroken that the pandemic is stealing yet another experience from my students, one that this year’s juniors won’t even know they are missing. I can’t wait to get back in my classroom and inspire my unwitting poets next year. In the meantime, I am focused on writing my own poetry. I’ve never been published before—at least not professionally, so I am looking forward to submitting some work and getting valuable feedback from publishers. I find poetry so cathartic, and I hope to inspire that feeling in my students as well. I encourage you as teachers to let your students play with words. We often times are so focused on the analysis and scholarly study of poetry, that it’s easy to suck the joy out of it. And I postulate that poetry should bring joy, both to the reader and the poet. If you are interested in exploring Metaphor Dice for your own classroom, you can find them here or on Amazon. If you would like to know more about my own poetry project, please feel free to contact me via email. I will happily share my resources. About the Author

Amanda Little is a mother of two and a native Salinan who has been teaching ELA and Public Speaking to juniors and seniors at Ell-Saline MS/HS for the last 7 years. She earned her bachelor's degree from Kansas Wesleyan University and recently earned her masters through the summer MA program at Fort Hays State University, graduating Phi Kappa Phi. When she isn't at school serving her students, she is serving through the church, scrolling Facebook far too much, reading books that are past due from the library, and writing poetry. Her first publication was published in the local newspaper when she was in kindergarten, a short poem about Christmas trees. You can contact her via e-mail at alittle@ellsaline.org. By Matthew Friedrichs  As a second-year ELA teacher, there are so many things that I don’t know. One thing, however, that seemed intuitive when I entered the classroom after nearly 20 years as an editor, was the tie between images and words. Great readers effortlessly form mental images as they dance through the words on the page. Unfortunately, many of my eighth-graders, and even some seniors, struggle with that mental animation. At the same time, my photography students in grades nine through 12, often scuffle when asked to translate visual information into words. As a result, I’ve worked hard with both groups to bridge those communication gaps by juxtaposing and connecting visual and written artworks. During the fall 2019 KATE conference, Deborah Eades (@DeborahEades10) presented about using portraiture in the ELA classroom. I could only shake my head up and down in violent yeses as she provided a framework for many of the methods I have tried. Eades shared what she had learned during a Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery training on the topic of stimulating nuanced student conversations guided by pictures. One example of a portrait Eades shared that would spark great conversation in a classroom is Roger Shimomura’s, Shimomura Crossing the Delaware. The painting references the famous image of General George Washington during the Revolutionary War. Close study could be paired with art and/or history classes. The image mixes traditional Japanese styles with pop art and more realistic depictions, and also draws upon Shimomura’s personal history of being imprisoned along with other Japanese-Americans during World War II. Including this painting in my teaching excited me, for while it offers strong, cross-curricular ties, it also offers a deep Kansas connection. Work by Shimomura is on display throughout the state. I am a firm believer that standing in front of art often is more transcendent than looking at an online or print image. Thus, Shimomura, who taught at the University of Kansas from 1969 to 2004, is a great painter for close study and first-hand lessons. These nearby museums hold his works: