|

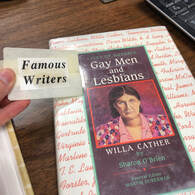

By Nathan Whitman  The censorship my student and I discovered The censorship my student and I discovered With lists in hand, the search underway, we scoured the library for the book for her research project. Now, our school library wasn’t large – barely a shoebox of a room, and yet the text eluded us. Right before the bell was to ring, my student approached me. “Mr. Whitman, is this it?” she asked. I looked at the call number: it was, but the title was off. On the computer print off, the title read Famous Writers: Willa Cather. The cover looked to match, but the spine told a different story: Lives of Notable Gay Men and Lesbians: Willa Cather. It was then we realized what we held in our hands: censorship, erasure of LGBTQ+ identities in our school. I decided to liberate this book, take it back out of the closet – for lack of a better phrase. While my student looked for other items on her list, I peeled away the label that some staff member generations before had decided would make this text “school-appropriate.” My colleagues in larger, more diverse school districts may find this shocking, but parts of rural Kansas are still playing the catchup game on diversity and inclusion, a game that many community members would be happy to see our students lose. According to the most recent GLSEN “2019 State Snapshot: School Climate for LGBTQ Students in Kansas” survey, only 52% of LGBTQ students report having inclusive library resources. Worse yet, only 12% reported LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. In contrast to the 2017 GLSEN Kansas State Snapshot, only 51% of students reported having inclusive library resources; 17% reported LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. From this two-year difference certain conclusions are clear: representation is stagnant in a best-case scenario in our libraries, but that 5% decrease in classroom representation is undeniable proof that Kansas educators must do better. However, I would be remiss to say that this lack of representation is – as a whole – purposefully malign. The publishing industry only recently started to actively pursue works by LGBTQ+ authors or books that have LGBTQ+ characters and themes; furthermore, tracking and monitoring LGBTQ+ representation in the publishing industry is still in its infancy. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center’s (CCBC) “2017 Statistics on LGBTQ+ Literature for Children and Teens” found that of 3,700 books, 136 (3.68%) had significant LGBTQ+ content, which “includes books with LGBTQ+ primary or secondary characters, LGBTQ+ families, nonfiction about LGBTQ+ people or topics, and . . . ‘LGBTQ+ metaphor’ books.” Some educators may not know where to begin looking for LGBTQ+ texts or what the best texts to include are. Luckily, resources for them are growing by the day, such as the HRC’s Welcoming Schools initiative, Scholastic’s “10 LGBT+ Books for Every Child’s Bookshelf”, Learning for Justice’s “LGBTQ Library”, the lists at LGBTQ Reads, and the Rainbow Library. Nevertheless, I know that fighting for a diverse curriculum, let alone diverse library, is also a challenge that educators and librarians face. This comes from personal experience. When I first joined my former district, the librarian and I attempted to order a slew of award-winning books that also reflected diverse communities, including those of sexual orientation and gender identity: purchase order denied. Yes, something is rotten in the state of education and literacy, and the pattern is undeniable when looking at the American Library Association’s “Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2019”. Can you spot the pattern? 1. George by Alex Gino 2. Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out by Susan Kuklin 3. A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo by Jill Twiss, illustrated by EG Keller 4. Sex is a Funny Word by Cory Silverberg, illustrated by Fiona Smyth 5. Prince & Knight by Daniel Haack, illustrated by Stevie Lewis 6. I Am Jazz by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings, illustrated by Shelagh McNicholas 7. The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood 8. Drama written and illustrated by Raina Telgemeier 9. Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling 10. And Tango Makes Three by Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson, illustrated by Henry Cole Did you figure it out? If not, here’s an overly simplified breakdown. Americans are terrified of their children becoming one of four things: gay, feminists, witches; or gay, feminist witches. Jokes aside, these challenges come from our communities. The most frequent reasons for seeking to ban seven of these ten books? LGBTQIA+ content. Moreover, 43% were banned specifically because of content on trans or gender identities, and 43% were banned due to conflicts with religious or “traditional” family values. Some bans even continue to perpetuate the harmful myth that LGBTQIA+ identities are an illness, sin, or something into which children might be indoctrinated: 43%. I’ve seen this myth – one debunked by the Southern Poverty Law Center – perpetuated in many schools and communities. Furthermore, the American Academy of Pediatrics all agree with research: people do not choose to be LGBTQ+, and it is caused by genetic and environmental factors. This includes gender identity. When students have asked me or the counselor for LGBTQ+ books, we’ve helped them find copies of age-appropriate texts, but sometimes we receive the books back from home with a note that the child shouldn’t read it because it may turn them gay, or that the family doesn’t approve of the content on religious reasons. I’ve even had parents express concern that I was teaching Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson through a queer analytical perspective. Have you read much of Whitman’s poetry or Dickinson’s letters to Susan Gilbert? If you’ve ever read anything beyond Whitman’s American nationalism and Dickinson’s death or religious poems, they’re pretty gay. Just as reading from the perspective a person of color’s experience won’t turn a child into a different race, reading the perspectives of a queer person or considering classical class texts through a queer lens won’t turn a child gay. But, I can tell you one thing it will do: it will help them build empathy. It will help them understand others – people not like them. And, if I’m lucky, some may see themselves reflected. To be frank, there is nothing wrong with coming from a religious family or one that has “traditional” family values. Those are my roots. What is wrong is when religious communities and families want to create a parochial school in a public institution by censoring texts and curriculum. Public schools serve just that: the public. Everyone. Even LGBTQ+ people. Plenty of texts in the ELA canon feature nuclear “traditional” families or heterosexual relationships (Romeo & Juliet, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Great Gatsby, The Hunger Games, The Odyssey, Pride and Prejudice, Sense & Sensibility, A Tale of Two Cities, Their Eyes Were Watching God – all say, “Hello!”); many feature or reference Judeo-Christian ideas, morals, and philosophies (A Christmas Carol, The Crucible, The Scarlet Letter, Dickinson’s religious poems, and nearly any early-American text in a junior English textbook also say, “Wassup?”). What we are not asking for is their erasure: we are asking for our equal representation. If that disturbs you, a school system that represents everyone, here’s a list of private Kansas schools. As a friendly reminder, private education does not always have to provide services to people with disabilities, LGBTQ+ students, or students of color. In short: no federal funding? Fewer protections.  The texts included in my Rainbow Library The texts included in my Rainbow Library While protections are growing for our LGBTQ+ students, there’s still much work to be done, and it starts with the teachers. Often, we make purchases at our own expense, but sometimes blessings come our way, like that aforementioned Rainbow Library. When a representative from GLSEN Kansas posted that this nonprofit collaborative was happening, that I could obtain free LGBTQ+ books for my school’s library, I jumped at the chance. Purchase orders be damned! Willa Cather was going to have company. Upon receiving the texts, I created a display in my classroom, performed a book talk, and I asked each class of students the following questions on an anonymous survey. In total, about 66% of high school students completed the survey, and these were my findings. Question 1: Do any of these books interest you? Why and why not?

Question 2: Should students have access to books like these in a school library or classroom library? Why or why not? Despite religious convictions, 100% of students surveyed thought that the books belonged in a school or classroom library. A few of their most poignant statements are below. Only spelling, punctuation, and capitalization have been corrected for readability.

If only their parents and communities knew their thoughts and the value of these texts to our students. Unfortunately, many students feel they can’t have these conversations with their parents. They fear what might happen: disapproval, conversion therapy, disownment. As we tell our LGBTQ+ students, “It gets better,” we must also remind ourselves that it is getting better, and we teachers can make it better. If I’m certain of one thing, it is this: there is hope for the future, and it’s sitting in my library and in the desks of my students.  About the Author Nathan Whitman is the current Kansas Association of Teachers of English President. He teaches English at Derby High School USD 260 and is also an adjunct professor at Hutchinson Community College and WSU Tech. Twitter: @writerwhitman Instagram: @writerwhitman By Dr. Katie Cramer ***The following post was originally posted on Dr. Cramer's personal blog, which can be found here. In her groundbreaking book Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy, Dr. Gholdy Muhammad convincingly argues that Black and Brown excellence has been erased from our curriculums and that contemporary education prioritizes the teaching of basic skills to the detriment of our students, particularly our students of color. To address these significant issues, Muhammad (2020) developed the Historically Responsive Literacy (HRL) Framework based on her research on Black Literary Societies of the early 1800s in which “literacy was not just for self-enjoyment or fulfillment, it was tied to action and efforts to shape the sociopolitical landscape of a country that was founded on oppression” (p. 22). The four pursuits of the HRL Framework The HRL Framework features four interwoven pursuits that also align with those of the Black Literary Societies of the early 19th century:

In her book, Muhammad argues that the HRL Framework is useful in all content areas at all levels. She explores each of the four pursuits in detail and convincingly argues the value of each one. For example, in describing identity development, Muhammad (2020) reminds us that identity was stripped from enslaved Africans and so it is vital that people of color know themselves in order to tell their own stories (p. 64). We must encourage our students to speak for themselves, and we must listen. We must also interrogate and resist our own deficit thinking (e.g., labeling students first/only as “at risk,” “defiant, “unmotivated, “tier 3”), and instead take an appreciative stance toward their existing literacies (Bomer, 2011, p. 21). We must check our (colleagues’) bias when speaking about students who have been and continue to be marginalized in schools. We must listen to Muhammad’s words: “I have never met an unmotivated child; I have, however, ‘met’ unmotivating curriculum and instruction” (2020, p. 65). Indeed, our students’ identity stories must begin with their excellence (Muhammad, 2020, p. 67). Erasure of Black and Brown Excellence Dr. Muhammad convincingly argues that knowledge of Black Literary Societies and Black and Brown excellence has been erased from our curriculums throughout PreK-16, including in teacher education programs. Like Larry Ferlazzo (2020), I am embarrassed to admit that I had never heard of Black Literary Societies before reading her book. She urges teacher educators (those who prepare future teachers) toward the following pursuits:

Exploring the HRL Framework As teachers (at all levels), we must interrogate our own practice using the HRL framework, asking ourselves for each pursuit: “Where is the evidence in my practice?” and “What are my goals for improvement?” To engage in this work, I urge you to review questions for reflection from Dr. Muhammad that accompany each pursuit and consider how you might revise (or design new) lessons/units to fulfill these pursuits—and engage in your own intellectual development by exploring Dr. Muhammad’s work further (see links the list of references below): Identity

Skills

Intellect

Criticality

Friends, we must interrogate our curriculums—the ones we design AND the ones provided by our school districts. As Dr. Muhammad (2021) reminds us, we “have enough genius to do this work.” So let us begin. References Bomer, R. (2011). Building adolescent literacy in today’s English classrooms. Heinemann. Ferlazzo, L. (2020 Jan. 28). Author interview with Dr. Gholdy Muhammad: “Cultivating genius.” Edweek. https://www.edweek.org Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. Scholastic. Muhammad, G. (2021 Mar. 17). Cultivating genius and joy: An equity model for culturally and historically responsive literacy [Webinar]. WRITE Center. https://www.writecenter.org/webinars.html Further reading Learn more about Dr. Gholdy Muhammad by viewing her faculty profile at Georgia State University. For more information on Black Literary Societies, read Cultivating Genius and/or Forgotten readers: Recovering the lost history of African American literary societies (2002) by Elizabeth McHenry, the first chapter of which is available HERE.  About the Author Katherine Mason Cramer is a former middle school English teacher and a professor of English Education at Wichita State University. She has been a KATE member since 2010 and an NCTE member since 2000. She serves on the KATE Executive Board, and has served as Editor of Kansas English since 2017. She can be reached at Katie.Cramer@wichita.edu. |

Message from the EditorWelcome! We're glad you are here! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed