|

Long sought and finally happening, KATE book clubs are another way for ELA educators to connect across the state! Each month, we will focus on 1-2 books. Meetings will be held either once (at the end of a reading) or bi-weekly (for longer texts). Open to any KATE member as participant or facilitator, we hope that these clubs not only entertain but also inform and inspire you.

Following a book club, the club facilitator will write a post for KATE Blog reviewing the text per feedback from participants. A KATE Blog book review should containing the following elements:

If you would like to participate in a book club, please check out offerings and register via the Online Meetings portal. KATE member password required. This password can be found via our monthly member newsletters, or you can contact the KATE President to check and verify your membership status. If you would like to host or suggest a book club, please email KATE Blog Editor Michaela Liebst.

0 Comments

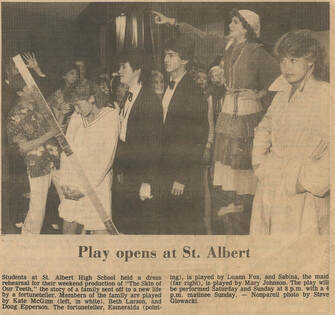

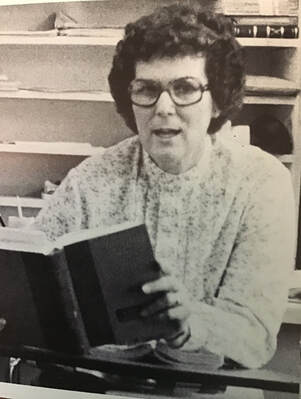

By LuAnn Fox  Ms. Lin Holder after the last show LuAnn ever performed with her. Photo Credit: Beth Larsen Champion Ms. Lin Holder after the last show LuAnn ever performed with her. Photo Credit: Beth Larsen Champion I found myself perched anxiously on the sofa in the anteroom of the women’s faculty restroom at the high school with my drama teacher right after I had done the deed. She settled into the sofa—a weird place to have a conversation, but then I was not a stranger to weird conversations. We were at play practice and the faculty women’s bathroom was directly across the hall from the old stage door. Actually, we were finished, but I had stayed to go over the blocking or to run the lines again with my teacher, who usually seemed willing. I was a jock-turned-drama-geek because I had to do something, something, after I couldn’t run the cemeteries for sports conditioning anymore. I’d daily cinch my belt around those ‘80s “mom jeans” to see if I’d made any progress in getting it tighter. I’d lay down nightly to gauge how the hip bones jutted against the flesh. I repeated mantras in my head, and sometimes almost aloud, as methodically as my own students years later would play with Theraputty or fidget spinners. When I threw myself against the heavy stage door on my way to the restroom, the drama teacher noticed, tossing out “You could have a sandwich or something,” in the same seemingly casual way you’d say “good night” at the end of an encounter. And then I had gone and done the deed, like so many times, like I was getting good at. But since blood lately dripped from my mouth into the toilet bowl, I was alarmed after and in fiery racking pain. Someone I trusted needed to know my painful dirty secret, and I decided to tell that drama teacher--Ms. Lin Holder. She was patient with light eyes and dark long hair, reminding me of Judy Collins, the folk singer I’d seen albums of when she was young. “Ms.” was the preferred title, even though she never called out any student for slipping with “Mrs.” It’s easy to do, with so many “Mrs.” around. Tall and imposing, she was striking with all that long unkempt Judy Collins hair, a key to her past. She’d flunked out of college because she’d had “better things to do” than go to class back then. She had sit-ins, protests, demonstrations, and rallies to attend—all the brothers were taken, disappearing into the jungles of Viet Nam and either never returning or returning changed forever. In her age band were the fighters, the lost, the finders of voices in a rapidly changing landscape. Ms. Holder knew all the peace songs, the protest songs, and the scarring of the betrayal of that era. She attended college later and graduated at the very top of her class. By the time I knew her, she had powered through graduate school and taught me the word extrapolated, because that’s what happened to her entrance examination scores: extrapolated from the national average, so as not to skew it.  LuAnn and others performing in a play directed by Ms. Holder, called "The Skin of Our Teeth." Photo Credit: Beth Champion Larsen LuAnn and others performing in a play directed by Ms. Holder, called "The Skin of Our Teeth." Photo Credit: Beth Champion Larsen So I told her that night in the anteroom, after shakily making her promise not to tell anyone. She weighed something invisibly and then lied to me. It was the best lie ever told to me. I revealed an alternating sneaky starvation with even sneakier throwing up, and I feared I had done serious harm to my throat, among other things. (I had.) Of course this was the landscape of a full-blown eating disorder; I had all the textbook causes that birthed the symptoms. We just didn’t have the knowledge nor those words for it then in the newly-minted 1980s. In telling my teacher, I felt almost physically lighter in that moment. Something weighty had been expelled and hung between us, yet I felt that perhaps I could see more of my problem, and by extension, grope toward a solution. For the first time something like it seemed possible—perhaps. And then the very next day, she told the administration. Of course she had to. But she miscalculated, there in the office at my small parochial school. She told them I was in certain trouble (and I was as I skeletally moved across my classes) and that she wanted to be the one to tell both me and my conflicted parents that I would need to leave my high school for an extended stay at the hospital. She was the one I had trusted—had loved, Ms. Holder reasoned. She should break the news to me. She could explain that I would need to leave the place where I was working doggedly for good grades and scholarships that would open the gateway to college. She would explain that it was a matter of my life, so that I would understand. But the administration simply thanked her for her service and said they’d take it from there. Lin Holder was shut out of the equation. I walked by the office and saw with my own eyes her red face and gesticulations and wondered why she was vehemently arguing with the principal. Within the hour, I was whisked away from my school--as abruptly as the spectre of COVID-19’s descent whisked away all of our students—for an unknown period of time. Within the next hour, I was deposited in a hospital—dumped--much like Haley Joel Osmont’s character in the movie A.I. is dumped into the woods. I was beyond panicked in a place that didn’t know then how to treat eating disorders—with people all around me trying (and failing) to handle me. I knew Ms. Holder was the culprit. If I had just shut my mouth . . . but too much blood and destruction came out of it with the gagging. She came to the hospital after work. I wouldn’t see her, like a prisoner who declines the visitor because it is the only power they have. Still she came. She came every day until I would see her. She wore me down. She gave me my homework. She gave me news: I had won this or that scholarship, I had maintained my high grades. She had nominated me for other awards that I had won. I was a National Merit Scholar, and I was one of two people who had won a national scholarship through my father’s work. She was my conduit to the world outside my ward, and she came every day. My first words to her were not of scholarships and awards, but of anger at her betrayal: her utter betrayal that led to me being caged. She took it, listened to it all. Just sat there. Didn’t censor me. Then, she explained, telling me why she lied, that she knew that was the only way for me to open up about the deadly thing I was doing that I didn’t apparently hide all that well. That she simply had to tell the school administration. This was a legal matter. And finally, that she had fought—oh, how she had fought—to be the one to see it all the way through, to help me, and my parents, by having us hear from her what help I needed. But it had all been summarily stripped from her, and she was dismissed. I had seen that last part myself, although I didn’t know it at the time. She told me that she knew that I was angry at her, and that, actually, she was fine with it. I was surprised. We were so close. Why wouldn’t she care? She explained in very direct and solemn terms that she was strong enough to bear my anger, that she would willingly do that any day, because the destructive cycle was interrupted and my life could be saved. She would rather have me hate her and live my life than love her and not be here. When I asked her why (as I thought my life was miserable—and no one ever accused me of never being dramatic), she told me that no matter how I felt now about myself, that this time would pass. That my life was one worth saving. I think of her to this day. She shaped me in ways I still learn about. I think I teach so passionately (no one’s ever accused me of not being intense, either) because I lost time in school. I lost valuable time. I teach with an urgency that I felt all through school, trying to get somewhere safe. I never want students to lose time or not feel safe, but we all contend with that in some way or another. I’ll never be the teacher Lin Holder was—saving a life--but I can strive to teach in ways I know she would approve of, taking the high road, doing the harder thing, keeping the welfare of students at the heart of the matter. And really, in tandem with teaching our craft, it’s these things that elevate teachers to being remembered long after the student becomes the teacher herself.  About the Author LuAnn Fox has been a high school teacher in the Olathe school district for 23 years, having taught almost 2500 students. She also works extensively with her local chapter of the National Writing Project and has done regional and national presentations and committee work. You can find her on Twitter, @theteach, or Instagram, @luann_fox. By Mark Fleske My dislike for Diet Mountain Dew verges on being distasteful. Seriously, it might be the second-worst drink that I can imagine - second only to anything with Kombucha in the title! For years, I wouldn’t dare to drink any diet soda, but when the numbers on my scale climbed to an embarrassing height, my weighty conscience drove me to drinking (diet that is). I could give or take other diet sodas. Diet Coke was palatable. Coke Zero was agreeable. And I would even claim Diet Cherry Pepsi as desirable. But Diet Mt. Dew? Diet Mountain Dew is detestable. This inordinate response likely stems from the fact that I love regular Mountain Dew so much. Mountain Dew is the drink of a generation for kids growing up in the ’80s and ’90s - my generation! As a kid, I have vivid memories of “Doing the Dew” and grabbing a cold can from my grandparents’ fully stocked refrigerator in their garage and finishing it in a few gulps. As a teenager, whoever was in charge of bringing supper (yes, we called the evening meal supper) to the harvest field would always have Mountain Dew as an option in the beat-up cooler in the trunk of the car or in the back of the pickup. I would make sure to grab a second can before getting back on the tractor to somehow sustain me for a few more hours of work before dark. Once I started driving to school, my favorite breakfast was a can of Mountain Dew and a Poptart as I navigated my Ford Ranger towards town. Compared to these vivid memories of my childhood and adolescence, Diet Mountain Dew feels (and tastes) like a watered-down version, a poor substitute for the real thing. I had a similar feeling earlier this week when I got off of what felt like my 1,000th Zoom call of the day. For extraverts like me, who have built their lives around purposefully positioning ourselves in the lives of others, Zoom calls feel like a watered-down version of a conversation, a meeting, a relationship; it is a poor substitute for the real thing. As a teacher, a coach, and a Young Life leader, I have built my career around engaging teenagers almost every hour of every day, in person. In person, I feel like I can make a difference in the lives of my students, players, and Young Life kids. I can celebrate their successes, even the minor ones; I can comfort their tears, even the ones they are fighting back; I can motivate their apathy, even when they really don’t want to; I can seek their hearts, even those who are always “fine”. While I can physically see their faces and utter the same phrases via Zoom, it’s not the same. It’s different. My favorite twenty minutes of my work week is a Zoom call a student schedules for 9:30 am every Tuesday. One of my students reserves that same time each week moments after I post the link to my office hours sign up (Google)sheet on Sunday evening. We have conferenced via Zoom every Tuesday morning of this continuous learning-inspired break from school. Throughout all of our conversations, she has asked precisely zero questions about class or about school in general. She simply wants to talk, so we talk. We talk about her parents’ recent divorce, how her younger brother is bright but bored and resists doing his homework, her newly found love of baking and delivering baked goods to classmates and teachers, the new depression-fighting techniques she has learned from her therapist, and pretty much anything else she wants to talk about. She has a need to talk, and I have learned that I have a need to listen. Unlike most Zoom meetings where we simply check tasks off of a list, where I lecture to a screen full of disengaged faces, where updates are read and comments are posted, I leave my Tuesday morning meeting with a joy and a sense of purpose; I feel filled up instead of poured out. The sad realization is that when I am allowed to teach, coach, and mentor teenagers in person, I experience similar, soul sustaining moments multiple times each day. During continuous learning, I am blessed to get it once a week at 9:30 am on Tuesdays. Don’t get me wrong; I am eternally thankful for the veritable geniuses who are responsible for the vision, the technology, and the technical support that allows people like me to connect with my extended family, my peers, and my students face to face in a virtual world. These digital connections have not only exponentially aided in the logistics of my job but they will also help emotionally sustain me until this new reality fades away into old memories. My emptiness as I clicked “Leave Meeting” is not a condemnation of Zoom, Google Hangout, FaceTime, or any other technology as much as it is an awareness that my soul is fulfilled by personal contact, intimate relationships, and communing together. The funny thing is that I get really excited when Zoom calls first start. Whether I am meeting one to one with a student or a Young Life kid or meeting with our school faculty or Cimarron Region Staff, a rush of endorphins kicks in. However, once the faces on my screen sign off, I’m left with a sadness, a realization of what I’m missing. Today has been difficult for me. I didn’t sign up to be a virtual teacher, to merely instruct my content from my home to the homes of students. I signed up to touch lives, in person, to experience successes or failures, with kids, to place myself in the middle of their lives. And that is hard to do on a Zoom call. At first, it kind of feels like I’m getting what I signed up for, but when I sign off, I realized I am simply settling for a substitute. I ordered a regular and ended up getting a diet. About the Author

My name is Mark Fleske, and I have taught at Andover Central High School in Andover, KS since 2001. My wife, Elizabeth, and I have three daughters, one of which will be graduating this month. Many of my reflections revolve around my emotions about Madison, my senior daughter, and her classmates. I have also coached boys basketball and tennis during my tenure at Central and have worked part-time for a ministry called Young Life for the past decade. By the Andover Central ELA Department  The Andover Central ELA Department - Back Row, L - R: Patrick Kennedy, Derek Tuttle, Mark Fleske - Front Row, L - R: Deborah Eades, Adrienne Stenholm, Briana Riddle, Allison Craig The Andover Central ELA Department - Back Row, L - R: Patrick Kennedy, Derek Tuttle, Mark Fleske - Front Row, L - R: Deborah Eades, Adrienne Stenholm, Briana Riddle, Allison Craig Patrick Kennedy would not want this blog post published. It would make him feel proud, but it might also make him a little uncomfortable. You see, Patrick Kennedy never set out to focus attention on himself. Instead, he focused attention on students and co-workers in a fun, profound, and unforgettable way, leaving a deep rooted and everlasting legacy. Patrick Kennedy died unexpectedly April 29, 2020. When we think of great English teachers to acknowledge during Teacher Appreciation Month, we would be remiss not to remember him. So, as his friends and department members, we share these words to honor his legacy. If you were to ask a co-worker or student about Mr. Kennedy, the initial answer might have something to do with his impressive collection of Converse shoes and matching shirts. It might have something to do with his ever expanding baseball hat collection or his messy desk. Inevitably, however, someone will mention Shout Out. Shout Out is just one of Mr. Kennedy’s legacies. It’s a little weekly show he developed and produced to highlight the accomplishments of students and staff. Every week, on his own time and with his own resources, he would gather a few students to “shout out” to teachers who had impacted them in positive ways, showcase students’ accomplishments, and create awareness of cool things happening at school. Each episode is filled with some kind of crazy antic: Mr. Kennedy dressed as a giant turkey for Thanksgiving,or a Star Wars character, or a pirate. While he created entertaining and innovative shows, the students were always the focus. He ended every show the same way, with a big, “I’m proud of you!” However, Shout Out is only a small sliver of what Mr. Kennedy left behind. We’ve all heard the saying that while people will forget what you said and forget what you did, they will never forget how you made them feel. How Mr. Kennedy made people feel is his real legacy. He had this intuitive nature of creating intimate connections. Though he was one of the most interesting people you could ever know, those connections weren’t about him. His interest was in you, in forming more than a friendship. It was more like a heart tether. With one dry-wit comment or hilarious deadpan expression, he could remind you of a dozen conversations you’d shared that you always came out of feeling better than when you went in. He had a knack for creating private jokes and in-depth conversations that lasted years, literally. With one colleague, he continued a habitual discussion of his extensive movie collection. With another he shared an ongoing love of literary puns, and with another, Star Wars quotes and sports highlights. For our department, he challenged us through example to raise the bar on our own work ethic, school involvement, instruction, and humility. Mr. Kennedy built close, friendly, caring connections with many students from the present and the past. No current or former student could walk by him in the hall between classes without the two of them exchanging some word or nonverbal cue, sometimes as a tradition established many months or even years prior. One particular student played rock-paper-scissors with Mr. Kennedy every single day on his way to another class. Because he had taught the young man in middle school and high school, who knows how long ago they established that tradition? This senior looked forward every day to the banter and competition of the simple game--and the connection to his former teacher. It was a daily reminder of a heart tether that transcended classroom walls. Mr. Kennedy was more than just a colleague; he was also a devout friend who socialized in many different groups. He would take trips with family or high school and college buddies to see as many baseball stadiums as he could, hoping to visit all fifty states eventually. He shared countless stories about wedding trips with friends. He would meet with former colleagues routinely to stay caught up, and he was always there to lend a supportive ear or give advice when asked to do so. Besides his love and care for people, Mr. Kennedy also had a love and care for the subject he taught. His love of the written word was not only contagious, it was also inspiring. He gushed over the Romantics and Whitman’s Leaves of Grass to the point where some of us started thinking maybe we’d missed something in our study of them. His students, even the reluctant readers, analyzed Gatsby in ways that would make even Fitzgerald take notice. When students graduated from his classes, they knew--really knew--clauses and phrases and poetic devices. They learned it because they understood that he expected them to. Mostly, though, they learned it because he made it accessible, interesting, and powerful.Their continued interest in stories carries on his legacy. The kids he coached looked to him for lessons in character as much as skill. His basketball boys knew the value of hard work and tenacity because he lived the message. They might miss the shot, but they would never miss the opportunity to learn the lesson. Nate Brightup, one of his Scholar’s Bowl students explained it this way, “Mr. Kennedy was someone who helped to center the team. It was like he could set us into the zone. If we thought we were hot stuff, he would remind us of our mistakes, not as a way to bring us down, but as a way to remember that there is always something to improve. The team shouldn't ever become complacent or comfortable with where we were at, we should keep on working.” Kate Calteaux studied with Mr. Kennedy in middle school. Her experience clarifies his inspiring nature. “For him to create an environment for me when I was thirteen or fourteen years old to understand the magic of English meant everything to me. It was a place where I could go and be a nerd and cut loose because I knew he wouldn’t mind. In fact, he would encourage that. He cared about every single student. No matter who you were, he was going to stick up for you, encourage you, and support you. And now, for me to want to become an English teacher, I owe a portion of that to him. He taught me that words and grammar are so much more than a subject. He made learning so exciting. He wouldn't want us to be sad. At the end of the day, he would say, ‘The show must go on.’” Mr. Kennedy is the kind of person whose presence made such a difference that his absence will make an even bigger one, but the heart tether remains strong, ensuring a continuance of inspiration. As we celebrate and remember him, we understand that, in fact, we are his legacy: his students who take with them into the world a love of language and a connection of caring and his co-workers who will attempt to fill the gap his absence leaves in our school community. As students figure out a way to carry on his Shout Out and create shoe drives in honor of his Converse obsession, and spread hashtags of his catchphrases through social media, we all know our show must go on. When someone pours into you like Mr. Kennedy has, we have the privilege and obligation to continue the legacy so that when he looks down on us, we know he’ll smile, raise a finger to the air and shout out, “I’m proud of you.” If you have a memory of Mr. Patrick Kennedy or any teacher whose legacy you have the privilege and obligation to continue, please add it to the comments, so we can continue to be inspired. About the Authors

The 2018 - 2020 Andover Central High School ELA department exemplifies teamwork. Though we were only fully together for two years, we enjoyed a camaraderie that can be rare in workplaces. We each had our specialty and our special interests, but it was our sincere respect for each other that held this team together. Sometimes, a person is blessed to be in the right place at the right time with the right people. That's what we had for two years. Going forward, it won't be exactly the same, but the fact is now that we've experienced it, we won't settle for less. By Dr. Elizabeth Minerva  Sara Lamar, my favorite high school teacher. Sara Lamar, my favorite high school teacher. My favorite English teacher kept a loaded water gun handy in case a student drifted off during her AP English class. She once removed a spoke-like film reel from its case, tiptoed across the room, and dropped the empty metal canister on the hard floor beside a sleeping student’s desk. We were all delighted, save the startled sleeper. She could be terrifying when she asked a question about one of our assigned books, such as Absalom, Absalom (Faulkner was her favorite). Her bright blue eyes would rove from face to face until she snagged someone. She expected a lot and would push for more if she saw a student verging on a significant realization. In no other class did I think or write as intently as I did during her in-class essays, and this was before I discovered caffeine. Her timed tests were a pure adrenal joy. Sara Lamar was my favorite high school teacher. She knew so much about the literature we read that she made each book seem essential to understanding humanity: James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness/Secret Sharer, Mark Twain’s The Mysterious Stranger, William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. Each new book was a revelation. She appreciated students’ ingenious ideas in class, guided us when we went off track, and encouraged our individual interpretations. I didn’t talk in class unless called upon. When she did call on me, it was because I was caught in her tractor beam gaze. One morning, Ms. Lamar gave the class a brief task and asked me to talk with her in the hallway. She had noticed that I’d seemed upset all week and wanted to know what was wrong. Voice shaking, I told her that my two-year crush had asked one of my best friends to the prom, which I learned when I called to ask if he wanted to go with me. This travesty led -- a few days later-- to the Latin teacher ordering me and the friend into the hall to deal with whatever was causing our furious note-passing. In the cell phone age, we would have spent the class period jamming our thumbs into our screens; then, our friends passed the folded up sheets of notebook paper hand to hand, all of them in on the conflict. This is a story I tell high school students with some self-deprecating humor (so much angsty material!), but at the time that boy mattered more than anything. Although teachers usually liked me -- quiet, conscientious, a copious taker of notes -- Ms. Lamar was the one who let me know that she saw me. We talked for a few minutes in the hallway. I cried; she listened and offered sympathy. It won’t always be like this, she assured me. When class resumed, I felt better -- not about the boy, but about being heard. My high school years occurred in a very different time. If a student knocked at the door of the teachers’ lounge, a resentful adult would appear in a slice of doorway, puffs of cigarette smoke wafting into the hall. “What is it?” the teacher would say tersely. On the south side of the school, there was a sloping student parking area where you couldn’t see inside the cars through the interior fog (“Freak Hill,” it was called). Freebird… Black and white students played on teams and served in student government together, but interracial dating was rare. Gay students, what? My American History teacher, a middle-aged woman with a perfect, shoulder-length flip, picked fights with our textbook’s prejudicial treatment of the south. Did she actually use the term “war of northern aggression”? Seniors had to pass a one-semester Americanism v. Communism class to graduate (no Bolsheviks in our bathrooms, thank you). I sat near the same people all four years in college prep track classes because alphabetical order was the obvious choice. Robin Montgomery, who often sat in front of or behind me depending on the class, maintained a 25-inch Levi waist size all four years. Although most administrators and teachers at Tallahassee’s Leon High School were kind, intelligent, and devoted, trauma-informed teaching would not have taken root in that red clay soil. If the houses on dirt roads that branched off Henderson Road really did not have central air and heating or other utilities, well, that’s just the way it was. Some people are poor. When baccalaureate was canceled my senior year due to complaints about holding a religious ceremony on school property, a civil war of words erupted; the church/state divide might’ve been legal but it wasn’t tradition. The school’s service clubs -- Key, Anchor, etc -- operated like fraternities and sororities with legacy members; many students who went on to public office started off in those exclusive groups. Life isn’t fair, is it? Deal with it, and hold your head high. We were a pride of lions. My high school was about the size of the one where I now teach in Wichita. My students don’t sit alphabetically in rows of desks, nor do the students in most of the ELA classrooms nearby. While ELA teachers still teach dead white male writers, the offerings are far more diverse these days. In addition, teachers are trained to know what ACES are and how they impact student performance, to recognize suicide warnings, to practice trauma-informed responses to student behavior. Individual relationships with students are essential because, without these connections, we can miss a key aspect of a student’s motivation. If you teach the material but don’t reach the students, what was accomplished? We are in this together and we care about our school community. Pride, Respect, Excellence. We are a sleuth of Grizzlies. When Ms. Lamar called me into the hallway that day, I already knew that she cared about me as a student. We had talked about my college choices. I’d stayed after class, questioning her about comments on my papers. She had supported me when I dropped typing to take Southern Lit with her senior year (the typing teacher was apoplectic -- a girl should have secretarial skills! What if I had children and my husband died and I had to support my family? I would need that second semester of typing). After my freshman year of college, I went back to see Ms. Lamar and she was eager to hear how I liked college, how my English professor had interpreted Faulkner. She had been sure I would enjoy college more than high school, and she was right. What I can take from all this as a teacher is obvious. Any teacher reading this knows how much those moments of recognition mean when a teenager just needs someone to look beyond the curriculum and see their face. My appreciation of Ms. Lamar is a call to be compassionate when students are struggling with life circumstances. Many of my students have far more challenging personal issues than a prom date. Students face serious mental health concerns, either their own or within their families. They might work a ridiculous number of hours at a low-paying job, watch younger siblings, bounce between households without a sense of stability, witness or participate in dangerous, risky behaviors. Schoolwork can be a lost concern when basic needs such as shelter and safety take precedence. Too, a boy or a girl who broke your heart is still cause for distress, as is the disappointing grade, the lunch spent alone in the Commons, the new glasses that no one noticed, the crap day that just keeps going. A moment of kind concern isn’t reserved for traumatic instances. And now, throw in a pandemic. During the COVID-19 crisis, reaching out to students has lacked the face-to-face barometer, the reward of seeing a teen smile or relax when they realize you just want to know how they are. In a professional learning session, a colleague suggested using Remind for short check-ins with students of concern, and I’ve found that to be a simple way to say “hey, how are you? Heard you’re working a lot of hours these days” or in some way let them know they are on my mind. Even students who do not end up turning in work will respond to a short personal inquiry. This isn’t, after all, about the student’s grade. So, I don’t wield a water gun or teach Faulkner, but I do still rely on the example Ms. Sara Lamar set. I see you. You matter to me. Are you okay?  About the Author Lizanne Minerva is an ELA teacher at Northwest High School in Wichita, KS. A native of North Florida, she is a Florida State University graduate. By Angie Powers  Examples of Mrs. Bushman's "plus" feedback. Examples of Mrs. Bushman's "plus" feedback. My grandmother was hard and sturdy. She taught me that being a woman, a human even, meant “sucking it up.” Life doesn’t care so much about your feelings; it will simply go on. She knew, with great certainty, that her job was to raise me as a strong woman. Enter Kay Bushman Haas. I knew, without really knowing, that Mrs. Bushman was a great teacher within moments of walking into her class as an introverted freshman. I didn’t know the accolades she had earned; I just knew that teaching came out of her pores. She effused her passion for language at the beginning of every class with our Daily Oral Language work--not something she mindlessly pulled from a book, oh no! She crafted our language workouts from student writing. She made nouns and verbs and adjectives and adverbs titalating. She invited us into Verona, Italy; Tuscumbia, Alabama; and even London, Oceania. I immersed myself in their pages, emerging after the last somehow expanded. I walked into her classroom knowing I wanted to be a teacher; I walked out knowing I wanted to be an English/Language Arts teacher like her. Lucky for me, Mrs. Bushman taught me again in Creative Writing sophomore year. I had been hoarding poems for years, so this was a class I desperately wanted to take. But, like most budding writers, I was terrified of sharing my writing. There was no way I was going to take that risk... well, until I learned she was the teacher. She taught me that my writing doesn’t have to be “good” or “bad,” but that writing is about those moments. Those punch-you-in-the-gut, jump-off-the-page moments. They can be fleeting, even buried. She shared those moments out of our writing anonymously in front of the class, finding the pearls in the mollusks of teenage angst, lonely sci-fi, and saccharine romance. I would sit--really perch--on the edge of my plastic seat, waiting to see if one of my moments would come out of her mouth. Sometimes, they did; sometimes, they didn’t. But that didn’t really matter because once she handed me my pages, they would be cluttered with plus signs, signifying that she saw every moment I offered. I would spend hours re-reading every moment she marked, trying to figure out what made that moment--or even me--worthy. I knew Mrs. Bushman was a strong woman. She was like my grandmother in that sense. They both weren’t tongue-holders; some might have even called them pushy, or worse. They both walked with a confidence that lacked arrogance to the discerning eye. So imagine my surprise when Mrs. Bushman smashed my grandmother’s definition of strength before my very eyes.  Kay and Angie at the Kansas Teacher of the Year banquet. Kay and Angie at the Kansas Teacher of the Year banquet. We spent a lot of time in Creative Writing journaling. I looked forward to the quiet time to write, finding asylum from the din of adolescence in the silence. I can’t remember if Mrs. Bushman shared her poem after one of our daily journaling sessions--or if it was something she shared at another time--but I remember her sharing. The poem was about loss. As she read, I constructed plus signs in my head for each of her moments. I was in awe that she shared so fiercely, reading her own words in front of a group of people--albeit a motley crew of drama-prone teens. And then it happened. Her voice cracked. I looked around, uncomfortable to stare directly at raw emotion. She wiped tears from her face. And then we continued class. Nobody knew that she had just incinerated my idea of strength. Over 25 years later, the yin and yang of strength and vulnerability still give me pause. I am more practiced at my grandmother’s strength: it carried me through long days as a teen mom and long nights of studying. It helped me through my first year of teaching while pregnant, strangely enough in the same teaching position that Mrs. Bushman left the year before. That kind of strength was about risk aversion: put your nose down, work hard, and never EVER let them see you sweat. But the vulnerable strength of Mrs. Bushman is the polar opposite of my grandmother’s and all about risk-taking. Like writing this. Those of us teaching today have the same power as Mrs. Bushman, who I now call my dear friend, Kay. Whether we teach from a classroom or a cart or our own homes, our lessons may begin with standards but they don’t end there. Our students learn a lot from us--not only from what we say but what we choose to not say. Kay had the strength to show her vulnerability. She took a risk, not knowing the impact on me--or my classmates. Her tears revealed her hurt; the crack of her voice told me that she knew she was going to be okay. Isn’t that what our students need to know right now? We all may hurt in different ways, but we can be okay. Social-emotional learning and resilience are hot topics in education, but master teachers of the past have grappled with them for centuries. Today, our challenge is to meet students’ needs in these areas during a time of uncertainty and amplified inequity. The weight of this challenge, no doubt, will require both my grandmother’s and Mrs. Bushman’s strengths. I’m putting my nose down, embracing my grandmother’s grit, by studying what it means to be an “emotion scientist” with Permission to Feel by Marc Brackett, Ph.D. However, I’m also living the truth of vulnerability. I can’t count the number of times I’ve felt the annoying sting of tears in my eyes for all of the things I’m missing at the end of my tumultuous twentieth year of teaching: my students, my colleagues, my family. Sometimes I’m angry. I’m furious that some of my students are ashamed of being who they are because of the anti-Asian sentiment COVID-19, and some of our nation’s leaders, have stoked. I resent the fact that some of my students need food, internet, or even a hug, and I cannot provide them all. But instead of feeling all of these things alone in my house, I choose to share them--even though you can’t hear the crack in my voice. I choose to share them because of a teacher--now friend--named Kay. And I know that, in the end, we can be okay.  About the Author Angie Powers is the mother of two strong humans. She's finishing her 20th year of teaching from her kitchen table in Olathe, KS. Her passion for advocacy has provided her many professional opportunities: NEA Board of Directors, Welcoming Schools facilitator, 2018 KTOY Team, Greater Kansas City Writing Project Fellowship, and National Board Certification. You can follow her on Twitter at @angsuperpowers |

Message from the EditorWelcome! We're glad you are here! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed