|

Exciting news! Join Wichita State's School of Education in their first annual colloquium featuring Dr. Crystal Kalinec-Craig from the University of Texas San Antonio. She'll discuss equity in education on March 19 at 5 p.m. in 209 Hubbard Hall. Dr. Kalinec-Craig is a leading voice in advocating for students' rights as learners. Don't miss this engaging discussion on creating humanizing classrooms! Follow this link to WSU's page to learn more!

0 Comments

February marks the kickoff the African American Read-In! Secondary educator Payton Dearmont prepares for celebrating the "diverse ideas, authors, and ultimately, literature" in her Freshman and Sophomore classes. By practicing culturally responsive pedagogy, Dearmont covers her goals of increasing engagement in the classroom, and emphasizing the need for students' sense of belonging.

Take a closer look at the cross-cultural curriculum and Dearmont's insights by clicking read more below! Last month, I had the opportunity to attend and present at the 2023 National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) Convention in Columbus, Ohio. Being a newer educator, this experience was one that I cannot recommend enough! That is not to say that educators (or just the general English lover) of all years of experience would not benefit from attending this conference. From the astounding number of vendors and authors in the convention center itself to the hundreds of breakout sessions over the four days that it took place, this was a fount of knowledge!...

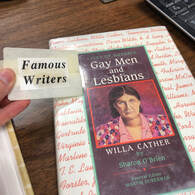

By Nathan Whitman  The censorship my student and I discovered The censorship my student and I discovered With lists in hand, the search underway, we scoured the library for the book for her research project. Now, our school library wasn’t large – barely a shoebox of a room, and yet the text eluded us. Right before the bell was to ring, my student approached me. “Mr. Whitman, is this it?” she asked. I looked at the call number: it was, but the title was off. On the computer print off, the title read Famous Writers: Willa Cather. The cover looked to match, but the spine told a different story: Lives of Notable Gay Men and Lesbians: Willa Cather. It was then we realized what we held in our hands: censorship, erasure of LGBTQ+ identities in our school. I decided to liberate this book, take it back out of the closet – for lack of a better phrase. While my student looked for other items on her list, I peeled away the label that some staff member generations before had decided would make this text “school-appropriate.” My colleagues in larger, more diverse school districts may find this shocking, but parts of rural Kansas are still playing the catchup game on diversity and inclusion, a game that many community members would be happy to see our students lose. According to the most recent GLSEN “2019 State Snapshot: School Climate for LGBTQ Students in Kansas” survey, only 52% of LGBTQ students report having inclusive library resources. Worse yet, only 12% reported LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. In contrast to the 2017 GLSEN Kansas State Snapshot, only 51% of students reported having inclusive library resources; 17% reported LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. From this two-year difference certain conclusions are clear: representation is stagnant in a best-case scenario in our libraries, but that 5% decrease in classroom representation is undeniable proof that Kansas educators must do better. However, I would be remiss to say that this lack of representation is – as a whole – purposefully malign. The publishing industry only recently started to actively pursue works by LGBTQ+ authors or books that have LGBTQ+ characters and themes; furthermore, tracking and monitoring LGBTQ+ representation in the publishing industry is still in its infancy. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center’s (CCBC) “2017 Statistics on LGBTQ+ Literature for Children and Teens” found that of 3,700 books, 136 (3.68%) had significant LGBTQ+ content, which “includes books with LGBTQ+ primary or secondary characters, LGBTQ+ families, nonfiction about LGBTQ+ people or topics, and . . . ‘LGBTQ+ metaphor’ books.” Some educators may not know where to begin looking for LGBTQ+ texts or what the best texts to include are. Luckily, resources for them are growing by the day, such as the HRC’s Welcoming Schools initiative, Scholastic’s “10 LGBT+ Books for Every Child’s Bookshelf”, Learning for Justice’s “LGBTQ Library”, the lists at LGBTQ Reads, and the Rainbow Library. Nevertheless, I know that fighting for a diverse curriculum, let alone diverse library, is also a challenge that educators and librarians face. This comes from personal experience. When I first joined my former district, the librarian and I attempted to order a slew of award-winning books that also reflected diverse communities, including those of sexual orientation and gender identity: purchase order denied. Yes, something is rotten in the state of education and literacy, and the pattern is undeniable when looking at the American Library Association’s “Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2019”. Can you spot the pattern? 1. George by Alex Gino 2. Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out by Susan Kuklin 3. A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo by Jill Twiss, illustrated by EG Keller 4. Sex is a Funny Word by Cory Silverberg, illustrated by Fiona Smyth 5. Prince & Knight by Daniel Haack, illustrated by Stevie Lewis 6. I Am Jazz by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings, illustrated by Shelagh McNicholas 7. The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood 8. Drama written and illustrated by Raina Telgemeier 9. Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling 10. And Tango Makes Three by Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson, illustrated by Henry Cole Did you figure it out? If not, here’s an overly simplified breakdown. Americans are terrified of their children becoming one of four things: gay, feminists, witches; or gay, feminist witches. Jokes aside, these challenges come from our communities. The most frequent reasons for seeking to ban seven of these ten books? LGBTQIA+ content. Moreover, 43% were banned specifically because of content on trans or gender identities, and 43% were banned due to conflicts with religious or “traditional” family values. Some bans even continue to perpetuate the harmful myth that LGBTQIA+ identities are an illness, sin, or something into which children might be indoctrinated: 43%. I’ve seen this myth – one debunked by the Southern Poverty Law Center – perpetuated in many schools and communities. Furthermore, the American Academy of Pediatrics all agree with research: people do not choose to be LGBTQ+, and it is caused by genetic and environmental factors. This includes gender identity. When students have asked me or the counselor for LGBTQ+ books, we’ve helped them find copies of age-appropriate texts, but sometimes we receive the books back from home with a note that the child shouldn’t read it because it may turn them gay, or that the family doesn’t approve of the content on religious reasons. I’ve even had parents express concern that I was teaching Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson through a queer analytical perspective. Have you read much of Whitman’s poetry or Dickinson’s letters to Susan Gilbert? If you’ve ever read anything beyond Whitman’s American nationalism and Dickinson’s death or religious poems, they’re pretty gay. Just as reading from the perspective a person of color’s experience won’t turn a child into a different race, reading the perspectives of a queer person or considering classical class texts through a queer lens won’t turn a child gay. But, I can tell you one thing it will do: it will help them build empathy. It will help them understand others – people not like them. And, if I’m lucky, some may see themselves reflected. To be frank, there is nothing wrong with coming from a religious family or one that has “traditional” family values. Those are my roots. What is wrong is when religious communities and families want to create a parochial school in a public institution by censoring texts and curriculum. Public schools serve just that: the public. Everyone. Even LGBTQ+ people. Plenty of texts in the ELA canon feature nuclear “traditional” families or heterosexual relationships (Romeo & Juliet, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Great Gatsby, The Hunger Games, The Odyssey, Pride and Prejudice, Sense & Sensibility, A Tale of Two Cities, Their Eyes Were Watching God – all say, “Hello!”); many feature or reference Judeo-Christian ideas, morals, and philosophies (A Christmas Carol, The Crucible, The Scarlet Letter, Dickinson’s religious poems, and nearly any early-American text in a junior English textbook also say, “Wassup?”). What we are not asking for is their erasure: we are asking for our equal representation. If that disturbs you, a school system that represents everyone, here’s a list of private Kansas schools. As a friendly reminder, private education does not always have to provide services to people with disabilities, LGBTQ+ students, or students of color. In short: no federal funding? Fewer protections.  The texts included in my Rainbow Library The texts included in my Rainbow Library While protections are growing for our LGBTQ+ students, there’s still much work to be done, and it starts with the teachers. Often, we make purchases at our own expense, but sometimes blessings come our way, like that aforementioned Rainbow Library. When a representative from GLSEN Kansas posted that this nonprofit collaborative was happening, that I could obtain free LGBTQ+ books for my school’s library, I jumped at the chance. Purchase orders be damned! Willa Cather was going to have company. Upon receiving the texts, I created a display in my classroom, performed a book talk, and I asked each class of students the following questions on an anonymous survey. In total, about 66% of high school students completed the survey, and these were my findings. Question 1: Do any of these books interest you? Why and why not?

Question 2: Should students have access to books like these in a school library or classroom library? Why or why not? Despite religious convictions, 100% of students surveyed thought that the books belonged in a school or classroom library. A few of their most poignant statements are below. Only spelling, punctuation, and capitalization have been corrected for readability.

If only their parents and communities knew their thoughts and the value of these texts to our students. Unfortunately, many students feel they can’t have these conversations with their parents. They fear what might happen: disapproval, conversion therapy, disownment. As we tell our LGBTQ+ students, “It gets better,” we must also remind ourselves that it is getting better, and we teachers can make it better. If I’m certain of one thing, it is this: there is hope for the future, and it’s sitting in my library and in the desks of my students.  About the Author Nathan Whitman is the current Kansas Association of Teachers of English President. He teaches English at Derby High School USD 260 and is also an adjunct professor at Hutchinson Community College and WSU Tech. Twitter: @writerwhitman Instagram: @writerwhitman By Dr. Katie Cramer ***The following post was originally posted on Dr. Cramer's personal blog, which can be found here. In her groundbreaking book Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy, Dr. Gholdy Muhammad convincingly argues that Black and Brown excellence has been erased from our curriculums and that contemporary education prioritizes the teaching of basic skills to the detriment of our students, particularly our students of color. To address these significant issues, Muhammad (2020) developed the Historically Responsive Literacy (HRL) Framework based on her research on Black Literary Societies of the early 1800s in which “literacy was not just for self-enjoyment or fulfillment, it was tied to action and efforts to shape the sociopolitical landscape of a country that was founded on oppression” (p. 22). The four pursuits of the HRL Framework The HRL Framework features four interwoven pursuits that also align with those of the Black Literary Societies of the early 19th century:

In her book, Muhammad argues that the HRL Framework is useful in all content areas at all levels. She explores each of the four pursuits in detail and convincingly argues the value of each one. For example, in describing identity development, Muhammad (2020) reminds us that identity was stripped from enslaved Africans and so it is vital that people of color know themselves in order to tell their own stories (p. 64). We must encourage our students to speak for themselves, and we must listen. We must also interrogate and resist our own deficit thinking (e.g., labeling students first/only as “at risk,” “defiant, “unmotivated, “tier 3”), and instead take an appreciative stance toward their existing literacies (Bomer, 2011, p. 21). We must check our (colleagues’) bias when speaking about students who have been and continue to be marginalized in schools. We must listen to Muhammad’s words: “I have never met an unmotivated child; I have, however, ‘met’ unmotivating curriculum and instruction” (2020, p. 65). Indeed, our students’ identity stories must begin with their excellence (Muhammad, 2020, p. 67). Erasure of Black and Brown Excellence Dr. Muhammad convincingly argues that knowledge of Black Literary Societies and Black and Brown excellence has been erased from our curriculums throughout PreK-16, including in teacher education programs. Like Larry Ferlazzo (2020), I am embarrassed to admit that I had never heard of Black Literary Societies before reading her book. She urges teacher educators (those who prepare future teachers) toward the following pursuits:

Exploring the HRL Framework As teachers (at all levels), we must interrogate our own practice using the HRL framework, asking ourselves for each pursuit: “Where is the evidence in my practice?” and “What are my goals for improvement?” To engage in this work, I urge you to review questions for reflection from Dr. Muhammad that accompany each pursuit and consider how you might revise (or design new) lessons/units to fulfill these pursuits—and engage in your own intellectual development by exploring Dr. Muhammad’s work further (see links the list of references below): Identity

Skills

Intellect

Criticality

Friends, we must interrogate our curriculums—the ones we design AND the ones provided by our school districts. As Dr. Muhammad (2021) reminds us, we “have enough genius to do this work.” So let us begin. References Bomer, R. (2011). Building adolescent literacy in today’s English classrooms. Heinemann. Ferlazzo, L. (2020 Jan. 28). Author interview with Dr. Gholdy Muhammad: “Cultivating genius.” Edweek. https://www.edweek.org Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating genius: An equity framework for culturally and historically responsive literacy. Scholastic. Muhammad, G. (2021 Mar. 17). Cultivating genius and joy: An equity model for culturally and historically responsive literacy [Webinar]. WRITE Center. https://www.writecenter.org/webinars.html Further reading Learn more about Dr. Gholdy Muhammad by viewing her faculty profile at Georgia State University. For more information on Black Literary Societies, read Cultivating Genius and/or Forgotten readers: Recovering the lost history of African American literary societies (2002) by Elizabeth McHenry, the first chapter of which is available HERE.  About the Author Katherine Mason Cramer is a former middle school English teacher and a professor of English Education at Wichita State University. She has been a KATE member since 2010 and an NCTE member since 2000. She serves on the KATE Executive Board, and has served as Editor of Kansas English since 2017. She can be reached at Katie.Cramer@wichita.edu. By Dr. Katie Cramer As a teacher educator, I have been preparing future middle and high school English teachers—first in Georgia and now in Kansas—for more than a decade. Since 2007, I have used position statements from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) to support my professional practice, particularly my decision to center sexual and gender diversity in my curriculum. When NCTE passed the Resolution on Strengthening Teacher Knowledge of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Issues in 2007, I was able to further defend my curricular inclusion of sexual and gender diversity in my English methods class against resistance from a small but vocal minority of my teacher candidates who argued that …

Aside from expressing my dismay at each of these claims (and my absolute horror at the last one)—as well as my relief that I’ve not heard teacher candidates express these views in the past 10 years—I will not belabor them. In fact, I have written about these challenges before, including in Kansas English (Mason & Harrell, 2012) and more recently in a chapter in Incorporating LGBTQ+ Identities in K-12 Curriculum and Policy (Cramer, 2020). Instead, in this piece, I want to remind all of us that we can be even more powerful in our teaching for social justice when we seek out support from our professional organizations at the state and national levels. What are position statements? For the past 50 years, NCTE has published position statements on a number of issues that guide and support our professional practice. According to NCTE, position statements “bring the latest thinking and research together to help define best practices, offer guidance for navigating challenges, and provide an expert voice to back up the thoughtful decisions teachers must make each day” (NCTE Position Statements). They begin as resolutions, crafted and submitted by a group of at least five NCTE members and reviewed by the NCTE Committee on Resolutions before being discussed and voted on at the Annual Convention and later ratified by NCTE membership. NCTE notes the value of both the process and the product on its resolutions page: “When a resolution is ratified it signals to members and the wider education community that these issues are top concerns. Most resolutions also come with research about and suggested solutions to the problem. As such, a resolution is a tool you can use as an educator to advocate for these issues, knowing you have the backing of a national organization in your stance.” (NCTE Resolutions) The oldest position statements NCTE lists on its website were discussed and voted on at the NCTE Annual Business Meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1970 and include fascinating and still relevant resolutions on …

More recently, NCTE membership has ratified statements that center sexual and gender diversity. During LGBTQ Pride Month, let’s turn our attention to two position statements that support our efforts to recognize and affirm sexual and gender diversity in our schools and curriculums. Resolution on Strengthening Teacher Knowledge of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Issues (2007) NCTE’s Resolution on Strengthening Teacher Knowledge of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Issues was ratified in November 2007 at the beginning of my career in teacher education, and it has provided the support I needed to center sexual and gender diversity in my teacher preparation curriculum. It states that “effective teacher preparation programs help teachers understand and meet their professional responsibilities, even when their personal beliefs seem in conflict with concepts of social justice” (NCTE, 2007). It advocates for the inclusion of LGBTQ+ studies in teacher education programs, even going so far as to advocate that accrediting bodies recognize the importance of the study of LGBTQ+ issues in such programs. This resolution/position statement not only strengthened individual faculty members’ rationales for the inclusion of sexual and gender diversity in their coursework, it also led to positive changes within the NCTE. Less than two years later in March 2009, English Journal published its first themed issue on sexual and gender diversity, and more recently, the NCTE formed the LGBTQ Advisory Committee on which I am currently serving my second term. Statement on Gender and Language (2018) In 2018, NCTE members ratified the Statement on Gender and Language, which evolved out of NCTE’s previous position statements on gender and language from 1978, 1985, and 2002. The most current iteration of this statement “builds on contemporary understandings of gender that include identities and expressions beyond a woman/man binary” (NCTE, 2018). This 12-page document—one of the longest NCTE position statements I’ve encountered—features a plethora of information to guide teachers’ understanding of gender diversity. It defines gender-expansive terminology; describes research-based recommendations for working with students, colleagues, and the broader professional community; and includes an annotated bibliography of resources to help us “use language to reflect the reality of gender diversity and support gender diverse students” (NCTE, 2018). Stay Tuned … This summer, I was invited by the NCTE Presidential Team to collaborate with colleagues across the U.S. to revise three statements on gender and gender diversity. Two of the statements are 25 and 30 years old, respectively, and they need considerable updating as conceptions of gender and sexuality—and the language we use to describe them—have evolved (and continue to evolve). This committee, under the leadership of Dr. Mollie Blackburn, is currently planning to address both sexual and gender diversity in curriculum design in our revisions, and we hope to have one or more statements ready for discussion and vote at the 2020 NCTE Convention, which will take place virtually this year. Your Next Steps I invite you to take some time this summer, as you reflect on your curriculum design and prepare for the next academic year, to engage in the following activities:

Alongside our state affiliate the Kansas Association of Teachers of English (KATE), NCTE’s vision is to empower English language arts teachers at all levels to “advance access, power, agency, affiliation, and impact for all learners” (NCTE About Us). NCTE’s position statements are just one of the many ways the organization enacts that vision. References Cramer, K.M. (2020). Addressing sexual and gender diversity in an English education teacher preparation program. In A. Sanders, L. Isbell & K. Dixon (Eds.), Incorporating LGBTQ+ identities in K-12 curriculum and policy (pp. 66-111). IGI Global. Mason, K. & Harrell, C. (2012). Searching for common ground: Two teachers discuss their support for and concerns about the inclusion of LGBTQ issues in English methods courses.” Kansas English, 95(1), 22-36. NCTE (n.d.). About us. https://ncte.org/about/ NCTE. (n.d.). Position statements. https://ncte.org/resources/position-statements/ NCTE. (n.d.). Resolutions. https://ncte.org/resources/position-statements/resolutions/ NCTE. (2007, November 30). Resolution on strengthening teacher knowledge of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) issues. https://ncte.org/statement/teacherknowledgelgbt/ NCTE. (2018, October 25). Statement on gender and language. https://ncte.org/statement/genderfairuseoflang/  About the Author Katherine Mason Cramer is a former middle school English teacher and a professor of English Education at Wichita State University. She has been a KATE member since 2010 and an NCTE member since 2000. She serves on the KATE Executive Board, and has served as Editor of Kansas English since 2017. She can be reached at Katie.Cramer@wichita.edu. By Tim Wilkins  In Billy Collins’ poem “Introduction to Poetry,” the poem’s speaker depicts what often occurs with poetry in American high schools. The poem, written in 1988, begins by sharing what most writers would prefer their readers to do with their poems. Collins’ speaker wants readers to “hold it up to the light,” “walk inside,” “feel the walls for a light switch,” and—most recreationally—“waterski across the surface of a poem.” These breezy, informal acts invite the reader to unwind with a poem. Loosen up, he seems to say. The students, however, take a different approach: But all they want to do is tie the poem to chair with rope and torture a confession out of it. They begin beating it with a hose to find out what it really means. I find that little has changed in our classrooms with regard to poetry since these words were penned. In my experience, students might approach poetry with scorn or reluctance or great intrigue; whatever their interest level though, at some point most will don their investigator caps and begin to question the poem for its “deeper meaning.” I can almost see the dangling yellow bulb and bare steel table of their mind’s interrogation room. Our students’ recognition that poetry offers a depth that most of our world passes over is certainly right. But if we lead them to believe that this is all poetry has to offer, then we withhold from them a world of enjoyment. I want to suggest that we as educators begin to present poetry as a pause, a pleasure, and a practice in creativity. In the midst of this COVID-19 pandemic, we need all three of these in our lives. What a perfect time to rediscover the wonder of poetry! Poetry as a Pause Three years ago, I decided to start each of my Honors English classes with the reading of a poem. I have maintained this practice in my classroom to this day, and it has become a great way to come together as a group before we begin our learning for the day. As a class, we don’t study the poem, examine it for meaning or metaphor, or even look at the text together. I simply read it aloud, then we move on. I call it Paused for a Poem. Poetry, I tell my classes, is really a pause from the unceasing rhythm of life to grab at a moment, at a brief glimpse of life, and relish it. Even the lineation of verse draws the reader back into the poem, pausing after each phrase and returning again to the moment in question. When I first introduced this practice to my students, I was worried they would find it hokey, childish, or simply a waste of time. And some probably do. But I can’t tell you how many times a student has connected with a particular poem, asked me afterward for more information about a poet, or made sure to remind me if I forgot to read one to begin our day. As I share poems with my students, I can see the tilt of the head or a focusing of their eyes that says, “I’m listening.” Sometimes there is even a whole-class exploratory discussion —a longing almost, to do something more with the poem of the day. Overall, I have been pleasantly surprised by their responses. When our school was shuttered amid this pandemic, one of the first questions I received from a student was, “Are we still going to have Pause for a Poem?” I have since started @pauseforapoem on Instagram to showcase the title, author, and audio reading of a daily poem for my students and for me. While we are apart, and in need of a pause from the isolation and distance, poetry lets us share together in a moment of verse -- to become, for a few seconds, a community looking out some window other than our own. Poetry as Pleasure Anyone who has ever written much poetry knows the work that goes into selecting the words, images, and punctuation that are just right for each situation and turn. Of course we can get out our dictionary of literary terms and lead students through an understanding of meter and scansion and lineation. But does being able to distinguish a trochee from a spondee really add to the students’ experience and understanding of a work? Don’t get me wrong, I love dissecting a poet’s labors as much as the next guy. But if our goal is to get students to pay attention to a poem and appreciate its depth and richness, I think focusing on these details is the wrong approach. The two areas of focus that I have found to help students grasp and appreciate poetry in the classroom are: 1) working with punctuation and 2) self-selecting impactful portions. When trying to emphasize the importance of punctuation in poetry, have students stand in a circle and read a common poem aloud, skipping readers at each punctuation mark. Every comma, dash, or period means a switch in the student reading the work. This exercise helps them grasp enjambment and end-stop, and what each contributes to the meaning and clarity of the language. Another exercise to try is to have students self-select a 2-4 line portion of the poem in question that they “like best.” This gives them the freedom to evaluate the words and images as critics, and then to reflect on why it resonated with them. I always get the most quality feedback and reflection from students using this exercise. They often share that they could personally connect to a description, or the words flowed well together, or they “just liked” the image or language used. That’s the pleasure of poetry. Poetry as Practice (in creativity) The last focus or exercise I’ll share is what I refer to as style swap. This exercise gives students an opportunity to try out their own poetic hand, but with reduced intimidation. I select a model poem that uses some structure or language that can be easily re-applied to something the student is interested in or familiar with. For instance, Ted Kooser’s poem “Splitting an Order” is a wonderful model poem for this exercise. In the poem, Kooser uses participle (-ing) verbs to begin phrases that describe the many delicate motions of a person splitting a sandwich with a romantic partner. After we read, annotate, and discuss the poem, I have students select an everyday common action that they are intimately familiar with (putting on make-up, making a Tik-Tok, changing the oil, entering a tree stand, etc.) and describe it using a style similar to Kooser’s litany of participle verbs. The results can be impressive, inspiring,and even revealing, for both you and your students. Engaging in this activity provides students with an opportunity to write their own open-form, expressive poetry, and shows them that poetry can be as innocuous and approachable as one chooses to make it. Below are some resources for applying the strategies I’ve mentioned. I hope you will turn to poetry in your personal life during this bizarre time of social distancing and voluntary isolation - go waterski across a poem perhaps. I also hope you consider ways to inject poetic experiences into your classroom for your students, to let them explore it without abusing it—teach them how to pause and appreciate a moment for all it has to show us. Recommended collections of easy readable poems: Good Poems series collected by Garrison Keiller; A Treasury of Poems compiled by Sarah Stuart; Best Loved Poems of the American People collected by Hazel Felleman; Poetry 180 and 180 More, both compiled by Billy Collins. Recommended poems for style swap exercise: - Ted Kooser: “Splitting an Order” “So This Is Nebraska” “Abandoned Farmhouse” - Walt Whitman: “I Hear America Singing” - Naomi Shihab Nye: “Full Day” “Famous” - Robert Hayden: “Those Winter Sundays” - Jane Kenyon: “Coming Home at Twilight in Late Summer” Comment below any other poems/works you enjoy utilizing in your classrooms! About the Author

Tim Wilkins teaches English at Abilene (KS) High School. He is currently in his tenth year as a Kansas educator. Besides exploring poetry, he spends his free time reading and being outdoors with his wife and son. Twitter: @considerthis_ Instagram: @pauseforapoem By April Pameticky  I am a poet and a writer. It’s taken me years to take ownership of those words, in large part because I so often considered those activities somehow frivolous, self-indulgent, or superfluous. I saw them as ‘extra’ to my other roles: teacher, wife, mother. But I find there is nothing ‘extra’ about engaging the world as a poet first; that it’s the lens by which I measure and experience everything. It’s how I reconcile injustice and how I make sense of the senseless. Poetry is how I find my way home, both spiritually and metaphorically. And it’s often how I reflect on my every day, ordinary life. While I loosely studied poetry in college, my primary focus had always been fiction. It was only about ten years ago that I started exploring and studying poetry on my own. The irony, of course, is that as an English teacher, didn’t I always love poetry? The answer is No. More often than not, I believed that Poetry [capital P on purpose] was actually somehow lofty and above me. Poetry was for the ascetics and more ‘literary,’ not for me, who read trashy urban fantasy novels all summer long. But while pregnant with my oldest daughter, I found myself nesting in unexpected ways, drawn to more creative expression, and reading in ways I had never bothered to before. It helped that some friends put more contemporary poetry in my hands. Today, I take comfort and solace in poems: Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me. 23 Psalm Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Do not go gentle into that good night –Dylan Thomas Poetry reminds us of perspective, like in the lines from Rae Armantrout’s “Thing:” We love our cat for her self regard is assiduous and bland, for she sits in the small patch of sun on our rug and licks her claws from all angles and it is far superior to "balanced reporting" though, of course, it is also the very same thing. Poets respond to the world with humanity, giving word to our fear and unrest. Rattle maintains the series Poets Respond, and poet Francesca Bell touches on our collective anxiety in her poem “Love in the Time of Covid-19.” She writes I held my hands steady in the water’s reassuring scald, trying and trying to save you. As teachers and educators, we have the opportunity to either spoil poetry for our students, or introduce them to something that will be their companion through life. My concern is that we often want to ‘unlock’ a poem, somehow divine its key, and then we expect our students to do the very same thing. We approach a poem as a Biology I student might a formaldehyde frog. I love how Elizabeth Alexander defines poetry with such concrete detail in “Ars Poetica #100: I Believe:” Poetry is what you find in the dirt in the corner, overhear on the bus. While poetry is both a craft and an artform, and there are certainly ‘rules’ and ‘conventions’ that apply (as anyone who has ever had to coach students through their own poetry revision process can attest), poems are also this wonderful opportunity to live with ambiguity. To grieve that we are no longer in our classrooms, but to celebrate that we are still teachers, that we can provide comfort and care to our students. So as we enter April and National Poetry Month, I want to encourage my fellow educators to give your students an opportunity to really engage with poems. The internet can be an amazing resource, even if an educator feels they don’t quite ‘get’ poetry. Take some direction from Dante di Stefano’s award-winning poem “Prompts (for High School Teachers Who Write Poetry” when he says Write the uncounted hours you spent fretting about the ones who cursed you out for keeping order. For those teaching remotely, the Dear Poet Project 2020 [Poetry.org] is an awesome opportunity to engage directly with poets. Students are encouraged to write letters after viewing the poets’ videos—two of my favorites are participating this year: Joy Harjo and Kwame Dawes. Poets read and discuss their works, and students can then respond. For educators wanting to embrace their inner poet, here are a couple of prompts to consider, but don’t feel you must limit yourself! We at KATE would love to read what you come up with. I want to encourage you to embrace your inner poet and to not strive so much for perfection or that ‘A’ poem. Instead, respond to where you are each day. There are some prompts provided below, as well as some further resources for inspiration. Prompts:

Resources:

Abstract Over the course of history, various groups have challenged, banned, and burned texts out of fear and the desire to control the thoughts and beliefs of a populace. Dictatorial regimes such as Hitler's Nazi-controlled Germany used "bonfires [to] 'cleanse' the German spirit of the 'un-German' influence of communist, pacifist, and, above all, Jewish thought" (Merveldt 524). Modern religious fundamentalism seeks to control a populace either through fear and indoctrination like the ultra-conservative, nearly-literal witch hunt of J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series when religious leaders of various Protestant denominations feared that the hit young adult book series would teach impressionable minds actual witchcraft. One of the most famous and still frequently taught banned books is Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In this paper the argument is made for the teaching of banned books by a case-analysis of Twain's text that considers the historical context, positive and negative aspects of the text, the harm of censorship, the value of free speech, and how frequently-challenged texts promote critical thinking for students. Author Biography

Nathan G. Whitman, Derby High School Nathan Whitman is an English teacher at Derby High School who has an MA in English, a BA in Secondary Education with an emphasis in English 6-12, and a BA in Creative Writing, as well as an endorsement in English to Speakers of Other Languages from Wichita State University. In addition to heading the school's GSA sponsor, he is also a founder of the Voices of Kansas journal published by the Kansas Association of Teachers of English, a 2014 Horizon Award Winner, and a Kansas Exemplary Educators Network Member. He can be reached at nwhitman@usd260.com. |

Message from the EditorWelcome! We're glad you are here! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed