|

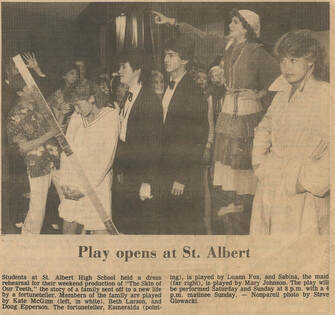

By LuAnn Fox  Ms. Lin Holder after the last show LuAnn ever performed with her. Photo Credit: Beth Larsen Champion Ms. Lin Holder after the last show LuAnn ever performed with her. Photo Credit: Beth Larsen Champion I found myself perched anxiously on the sofa in the anteroom of the women’s faculty restroom at the high school with my drama teacher right after I had done the deed. She settled into the sofa—a weird place to have a conversation, but then I was not a stranger to weird conversations. We were at play practice and the faculty women’s bathroom was directly across the hall from the old stage door. Actually, we were finished, but I had stayed to go over the blocking or to run the lines again with my teacher, who usually seemed willing. I was a jock-turned-drama-geek because I had to do something, something, after I couldn’t run the cemeteries for sports conditioning anymore. I’d daily cinch my belt around those ‘80s “mom jeans” to see if I’d made any progress in getting it tighter. I’d lay down nightly to gauge how the hip bones jutted against the flesh. I repeated mantras in my head, and sometimes almost aloud, as methodically as my own students years later would play with Theraputty or fidget spinners. When I threw myself against the heavy stage door on my way to the restroom, the drama teacher noticed, tossing out “You could have a sandwich or something,” in the same seemingly casual way you’d say “good night” at the end of an encounter. And then I had gone and done the deed, like so many times, like I was getting good at. But since blood lately dripped from my mouth into the toilet bowl, I was alarmed after and in fiery racking pain. Someone I trusted needed to know my painful dirty secret, and I decided to tell that drama teacher--Ms. Lin Holder. She was patient with light eyes and dark long hair, reminding me of Judy Collins, the folk singer I’d seen albums of when she was young. “Ms.” was the preferred title, even though she never called out any student for slipping with “Mrs.” It’s easy to do, with so many “Mrs.” around. Tall and imposing, she was striking with all that long unkempt Judy Collins hair, a key to her past. She’d flunked out of college because she’d had “better things to do” than go to class back then. She had sit-ins, protests, demonstrations, and rallies to attend—all the brothers were taken, disappearing into the jungles of Viet Nam and either never returning or returning changed forever. In her age band were the fighters, the lost, the finders of voices in a rapidly changing landscape. Ms. Holder knew all the peace songs, the protest songs, and the scarring of the betrayal of that era. She attended college later and graduated at the very top of her class. By the time I knew her, she had powered through graduate school and taught me the word extrapolated, because that’s what happened to her entrance examination scores: extrapolated from the national average, so as not to skew it.  LuAnn and others performing in a play directed by Ms. Holder, called "The Skin of Our Teeth." Photo Credit: Beth Champion Larsen LuAnn and others performing in a play directed by Ms. Holder, called "The Skin of Our Teeth." Photo Credit: Beth Champion Larsen So I told her that night in the anteroom, after shakily making her promise not to tell anyone. She weighed something invisibly and then lied to me. It was the best lie ever told to me. I revealed an alternating sneaky starvation with even sneakier throwing up, and I feared I had done serious harm to my throat, among other things. (I had.) Of course this was the landscape of a full-blown eating disorder; I had all the textbook causes that birthed the symptoms. We just didn’t have the knowledge nor those words for it then in the newly-minted 1980s. In telling my teacher, I felt almost physically lighter in that moment. Something weighty had been expelled and hung between us, yet I felt that perhaps I could see more of my problem, and by extension, grope toward a solution. For the first time something like it seemed possible—perhaps. And then the very next day, she told the administration. Of course she had to. But she miscalculated, there in the office at my small parochial school. She told them I was in certain trouble (and I was as I skeletally moved across my classes) and that she wanted to be the one to tell both me and my conflicted parents that I would need to leave my high school for an extended stay at the hospital. She was the one I had trusted—had loved, Ms. Holder reasoned. She should break the news to me. She could explain that I would need to leave the place where I was working doggedly for good grades and scholarships that would open the gateway to college. She would explain that it was a matter of my life, so that I would understand. But the administration simply thanked her for her service and said they’d take it from there. Lin Holder was shut out of the equation. I walked by the office and saw with my own eyes her red face and gesticulations and wondered why she was vehemently arguing with the principal. Within the hour, I was whisked away from my school--as abruptly as the spectre of COVID-19’s descent whisked away all of our students—for an unknown period of time. Within the next hour, I was deposited in a hospital—dumped--much like Haley Joel Osmont’s character in the movie A.I. is dumped into the woods. I was beyond panicked in a place that didn’t know then how to treat eating disorders—with people all around me trying (and failing) to handle me. I knew Ms. Holder was the culprit. If I had just shut my mouth . . . but too much blood and destruction came out of it with the gagging. She came to the hospital after work. I wouldn’t see her, like a prisoner who declines the visitor because it is the only power they have. Still she came. She came every day until I would see her. She wore me down. She gave me my homework. She gave me news: I had won this or that scholarship, I had maintained my high grades. She had nominated me for other awards that I had won. I was a National Merit Scholar, and I was one of two people who had won a national scholarship through my father’s work. She was my conduit to the world outside my ward, and she came every day. My first words to her were not of scholarships and awards, but of anger at her betrayal: her utter betrayal that led to me being caged. She took it, listened to it all. Just sat there. Didn’t censor me. Then, she explained, telling me why she lied, that she knew that was the only way for me to open up about the deadly thing I was doing that I didn’t apparently hide all that well. That she simply had to tell the school administration. This was a legal matter. And finally, that she had fought—oh, how she had fought—to be the one to see it all the way through, to help me, and my parents, by having us hear from her what help I needed. But it had all been summarily stripped from her, and she was dismissed. I had seen that last part myself, although I didn’t know it at the time. She told me that she knew that I was angry at her, and that, actually, she was fine with it. I was surprised. We were so close. Why wouldn’t she care? She explained in very direct and solemn terms that she was strong enough to bear my anger, that she would willingly do that any day, because the destructive cycle was interrupted and my life could be saved. She would rather have me hate her and live my life than love her and not be here. When I asked her why (as I thought my life was miserable—and no one ever accused me of never being dramatic), she told me that no matter how I felt now about myself, that this time would pass. That my life was one worth saving. I think of her to this day. She shaped me in ways I still learn about. I think I teach so passionately (no one’s ever accused me of not being intense, either) because I lost time in school. I lost valuable time. I teach with an urgency that I felt all through school, trying to get somewhere safe. I never want students to lose time or not feel safe, but we all contend with that in some way or another. I’ll never be the teacher Lin Holder was—saving a life--but I can strive to teach in ways I know she would approve of, taking the high road, doing the harder thing, keeping the welfare of students at the heart of the matter. And really, in tandem with teaching our craft, it’s these things that elevate teachers to being remembered long after the student becomes the teacher herself.  About the Author LuAnn Fox has been a high school teacher in the Olathe school district for 23 years, having taught almost 2500 students. She also works extensively with her local chapter of the National Writing Project and has done regional and national presentations and committee work. You can find her on Twitter, @theteach, or Instagram, @luann_fox.

3 Comments

Dr. Lin Holder

5/28/2020 03:18:06 pm

I remember that period of time very well. I can't say how much it means to me to hear your voice in this writing. I went of from this high school to a Doctoral program at the University of Kansas and spent the next 20 years of my career teaching at the university level. We teachers seldom know what happens to our students after they leave us, but I treasure still having Lu Ann still in my life as a friend.

Reply

Katie Cramer

5/29/2020 11:54:10 am

I am profoundly thankful that Ms. Holder was there for you when you chose to share your story, LuAnn, and thankful too that you are there for your students now. Thank you for sharing your story--with all of its brutal honesty--here in such a powerfully moving way. It is an honor to read this piece.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Message from the EditorWelcome! We're glad you are here! Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed