By Nathan Whitman  The censorship my student and I discovered The censorship my student and I discovered With lists in hand, the search underway, we scoured the library for the book for her research project. Now, our school library wasn’t large – barely a shoebox of a room, and yet the text eluded us. Right before the bell was to ring, my student approached me. “Mr. Whitman, is this it?” she asked. I looked at the call number: it was, but the title was off. On the computer print off, the title read Famous Writers: Willa Cather. The cover looked to match, but the spine told a different story: Lives of Notable Gay Men and Lesbians: Willa Cather. It was then we realized what we held in our hands: censorship, erasure of LGBTQ+ identities in our school. I decided to liberate this book, take it back out of the closet – for lack of a better phrase. While my student looked for other items on her list, I peeled away the label that some staff member generations before had decided would make this text “school-appropriate.” My colleagues in larger, more diverse school districts may find this shocking, but parts of rural Kansas are still playing the catchup game on diversity and inclusion, a game that many community members would be happy to see our students lose. According to the most recent GLSEN “2019 State Snapshot: School Climate for LGBTQ Students in Kansas” survey, only 52% of LGBTQ students report having inclusive library resources. Worse yet, only 12% reported LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. In contrast to the 2017 GLSEN Kansas State Snapshot, only 51% of students reported having inclusive library resources; 17% reported LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. From this two-year difference certain conclusions are clear: representation is stagnant in a best-case scenario in our libraries, but that 5% decrease in classroom representation is undeniable proof that Kansas educators must do better. However, I would be remiss to say that this lack of representation is – as a whole – purposefully malign. The publishing industry only recently started to actively pursue works by LGBTQ+ authors or books that have LGBTQ+ characters and themes; furthermore, tracking and monitoring LGBTQ+ representation in the publishing industry is still in its infancy. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center’s (CCBC) “2017 Statistics on LGBTQ+ Literature for Children and Teens” found that of 3,700 books, 136 (3.68%) had significant LGBTQ+ content, which “includes books with LGBTQ+ primary or secondary characters, LGBTQ+ families, nonfiction about LGBTQ+ people or topics, and . . . ‘LGBTQ+ metaphor’ books.” Some educators may not know where to begin looking for LGBTQ+ texts or what the best texts to include are. Luckily, resources for them are growing by the day, such as the HRC’s Welcoming Schools initiative, Scholastic’s “10 LGBT+ Books for Every Child’s Bookshelf”, Learning for Justice’s “LGBTQ Library”, the lists at LGBTQ Reads, and the Rainbow Library. Nevertheless, I know that fighting for a diverse curriculum, let alone diverse library, is also a challenge that educators and librarians face. This comes from personal experience. When I first joined my former district, the librarian and I attempted to order a slew of award-winning books that also reflected diverse communities, including those of sexual orientation and gender identity: purchase order denied. Yes, something is rotten in the state of education and literacy, and the pattern is undeniable when looking at the American Library Association’s “Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2019”. Can you spot the pattern? 1. George by Alex Gino 2. Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out by Susan Kuklin 3. A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo by Jill Twiss, illustrated by EG Keller 4. Sex is a Funny Word by Cory Silverberg, illustrated by Fiona Smyth 5. Prince & Knight by Daniel Haack, illustrated by Stevie Lewis 6. I Am Jazz by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings, illustrated by Shelagh McNicholas 7. The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood 8. Drama written and illustrated by Raina Telgemeier 9. Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling 10. And Tango Makes Three by Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson, illustrated by Henry Cole Did you figure it out? If not, here’s an overly simplified breakdown. Americans are terrified of their children becoming one of four things: gay, feminists, witches; or gay, feminist witches. Jokes aside, these challenges come from our communities. The most frequent reasons for seeking to ban seven of these ten books? LGBTQIA+ content. Moreover, 43% were banned specifically because of content on trans or gender identities, and 43% were banned due to conflicts with religious or “traditional” family values. Some bans even continue to perpetuate the harmful myth that LGBTQIA+ identities are an illness, sin, or something into which children might be indoctrinated: 43%. I’ve seen this myth – one debunked by the Southern Poverty Law Center – perpetuated in many schools and communities. Furthermore, the American Academy of Pediatrics all agree with research: people do not choose to be LGBTQ+, and it is caused by genetic and environmental factors. This includes gender identity. When students have asked me or the counselor for LGBTQ+ books, we’ve helped them find copies of age-appropriate texts, but sometimes we receive the books back from home with a note that the child shouldn’t read it because it may turn them gay, or that the family doesn’t approve of the content on religious reasons. I’ve even had parents express concern that I was teaching Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson through a queer analytical perspective. Have you read much of Whitman’s poetry or Dickinson’s letters to Susan Gilbert? If you’ve ever read anything beyond Whitman’s American nationalism and Dickinson’s death or religious poems, they’re pretty gay. Just as reading from the perspective a person of color’s experience won’t turn a child into a different race, reading the perspectives of a queer person or considering classical class texts through a queer lens won’t turn a child gay. But, I can tell you one thing it will do: it will help them build empathy. It will help them understand others – people not like them. And, if I’m lucky, some may see themselves reflected. To be frank, there is nothing wrong with coming from a religious family or one that has “traditional” family values. Those are my roots. What is wrong is when religious communities and families want to create a parochial school in a public institution by censoring texts and curriculum. Public schools serve just that: the public. Everyone. Even LGBTQ+ people. Plenty of texts in the ELA canon feature nuclear “traditional” families or heterosexual relationships (Romeo & Juliet, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Great Gatsby, The Hunger Games, The Odyssey, Pride and Prejudice, Sense & Sensibility, A Tale of Two Cities, Their Eyes Were Watching God – all say, “Hello!”); many feature or reference Judeo-Christian ideas, morals, and philosophies (A Christmas Carol, The Crucible, The Scarlet Letter, Dickinson’s religious poems, and nearly any early-American text in a junior English textbook also say, “Wassup?”). What we are not asking for is their erasure: we are asking for our equal representation. If that disturbs you, a school system that represents everyone, here’s a list of private Kansas schools. As a friendly reminder, private education does not always have to provide services to people with disabilities, LGBTQ+ students, or students of color. In short: no federal funding? Fewer protections.  The texts included in my Rainbow Library The texts included in my Rainbow Library While protections are growing for our LGBTQ+ students, there’s still much work to be done, and it starts with the teachers. Often, we make purchases at our own expense, but sometimes blessings come our way, like that aforementioned Rainbow Library. When a representative from GLSEN Kansas posted that this nonprofit collaborative was happening, that I could obtain free LGBTQ+ books for my school’s library, I jumped at the chance. Purchase orders be damned! Willa Cather was going to have company. Upon receiving the texts, I created a display in my classroom, performed a book talk, and I asked each class of students the following questions on an anonymous survey. In total, about 66% of high school students completed the survey, and these were my findings. Question 1: Do any of these books interest you? Why and why not?

Question 2: Should students have access to books like these in a school library or classroom library? Why or why not? Despite religious convictions, 100% of students surveyed thought that the books belonged in a school or classroom library. A few of their most poignant statements are below. Only spelling, punctuation, and capitalization have been corrected for readability.

If only their parents and communities knew their thoughts and the value of these texts to our students. Unfortunately, many students feel they can’t have these conversations with their parents. They fear what might happen: disapproval, conversion therapy, disownment. As we tell our LGBTQ+ students, “It gets better,” we must also remind ourselves that it is getting better, and we teachers can make it better. If I’m certain of one thing, it is this: there is hope for the future, and it’s sitting in my library and in the desks of my students.  About the Author Nathan Whitman is the current Kansas Association of Teachers of English President. He teaches English at Derby High School USD 260 and is also an adjunct professor at Hutchinson Community College and WSU Tech. Twitter: @writerwhitman Instagram: @writerwhitman by Michaela Liebst February 1st marks the first day of Black History Month, and with all of the events that have transpired over the past year, the celebration of black culture, influence, and pride feels more important than in years past. As educators, we are given a unique chance to highlight Black voices and bring them to the forefront of our curricular focus, exposing students to new concepts, ideas, and styles that they may have never experienced before. The KATE blog team feels passionately about this endeavor, and wants to aid you in bringing minority voices to the forefront. We are excited to provide a list of novels created by ELA teachers for both elementary and secondary grade levels that represent not only black characters, but other minority groups as well. We believe representation in literature is the key to equity and that creating a culture of understanding and inclusion within our classrooms is essential for helping to ease some of the dissonance that our communities, states, and nation are currently facing. We hope that this list inspires you to consider changing up the books you include in your curriculum, or to spice up your classroom library so that students have more access to a diverse range of books. I also encourage you to check out this blog post by Dr. Katie Cramer regarding the NCTE’s position statements “...to support curricular inclusion…” of all types of diversity. We are aware that combining the beliefs of your district with our nation’s current political climate could possibly deter you from wanting to provide access to these texts. However, we challenge you to start small and use the position statements as a way to advocate for the inclusion of these texts in your school buildings. Overall, we are excited for the opportunity to share this list with you and hope it inspires you to take advantage of this month to shake things up and prioritize the inclusion of all voices in your curriculum.  Book Suggestions for Secondary ELA Teachers BLACK HISTORY MONTH A Song of Wraiths and Ruins by Roseanne A. Brown: “The first in a fantasy duology inspired by West African folklore in which a grieving crown princess and a desperate refugee find themselves on a collision course to murder each other despite their growing attraction.” - suggested by Madison Jewell, Middle School ELA Teacher  Children of Blood and Bone by Tomi Adeyemi: “The first book in a series about a girl trying to restore magic. The monarchy tries to stop her.” - suggested by Madison Jewell. Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes: “A Black boy who was killed by a cop comes back as a ghost along with other black boys unjustly killed to make a difference.” - suggested by Krista May-Shackleford, Elementary Media Specialist  Slay by Brittney Morris: “Slay is a great read—A Black female protagonist has designed a game only open to Black players and keeps her role a secret. Her game has real world consequences and she suddenly finds herself over her head. I’m not a gamer but enjoyed it on so many levels.” - suggested by Lizanne Minerva, High School ELA teacher OTHER MINORITY GROUPS Middle-Eastern Culture -The Wrath and the Dawn by Renée Ahdieh: “Sharazad wants to get revenge on the boy-king who murders his new bride the night they marry. She chooses to marry him but comes to find he may not be like what he seems.” - suggested by Madison Jewell Latinx Culture - Into the Beautiful North by Luis Alberto Urrea: “Into the Beautiful North depicts fun, memorable characters who embark upon the dangerous journey to cross the border into America. This author has a unique way of combining humor, realistic teenage angst, and the serious issue of border crossing that keeps you turning pages and cheering for the heroine and seriously hoping for a sequel!” - , suggested by Deborah McNemee, High School ELA teacher LGBTQ+ - Cemetery Boys by Aiden Thomas: “A trans boy determined to prove his gender to his traditional Latinx family summons a ghost who refuses to leave” - suggested by Madison Jewell  Book Suggestions for Elementary Teachers BLACK HISTORY MONTH Fearless Mary by Tami Charles: “A real-life story that takes you back to the western front and hard dirt trails! Mary was the first woman stagecoach driver – the first African American woman stagecoach driver, in fact! This book shares some of her trailblazing experiences during her journeys carrying much-needed supplies and much-welcomed letters to people who had moved out west! Comic-book style illustrations make for a fun accompaniment to her story, including how her actions have influenced present-day mail delivery!” -suggested by Hannah Kraxberger, an elementary student teacher  The Day You Begin by Jacqueline Woodson: “The Day You Begin is about a young girl experiencing kindergarten for the first time. She is excited and nervous at the same time! Everyone seems so different. When the students share what they did over the summer, it’s hard for Angelina. She hears of all the wonderful stories of adventures her classmates went on while she stayed home and watched her sibling. Angelina finds her voice to share that she stayed home and, even though she didn’t experience any amazing stories, she MADE stories and that’s okay...Everyone has similarities and differences, and that’s what makes us beautiful!” - , suggested by Hannah Kraxberger CHILDREN W/ DISABILITIES Moses Goes to a Concert by Isaac Millman: “This book encourages the use of sign language throughout and includes accurate, colorful illustrations of how to sign the text. The book also exemplifies more subtle attributes of d/Deaf culture, such as some of the students waving to show their applause. The most admirable trait of Moses Goes to a Concert is the depiction of Moses and his friends as happy children who have typical lifestyles. The book does not focus on their disability as a problem to be fixed, and Mr. Samuels teaches them ways to thrive and enjoy activities in unique ways.” - suggested by Hannah Schoonover, an elementary student teacher Why Does Izzy Cover Her Ears? Dealing with Sensory Overload by Jennifer Veenendall: “This book details how confusing school can feel for a child who has a sensory processing disorder. This book could also help a teacher or parents realize that frequent misbehaviors often have an underlying cause. Classmates of a child like Izzy could better understand the reactions their classmate has and the interventions their classmate uses after reading this book. This book could also help a child with a sensory processing disorder explain how or what they are feeling in certain situations and give them a character with whom they can relate.” - suggested by Hannah Schoonover The Seeing Stick by Jane Yolen: “The Seeing Stick begins with Hwei Min feeling sad that she cannot see and shows her father trying to help fix her disability. However, as the book progresses it shows Hwei Min’s emotional transformation as she becomes comfortable “seeing” with her fingertips. The Seeing Stick gives the message that Hwei Min did not need to be “fixed.” However, she just needed the correct help and tools to allow her to embrace her disability.” - suggested by Hannah Schoonover We’ll Paint the Octopus Red by Stephanie Stuve-Bodeen: “Stephanie Stuve-Bodeen, author of We’ll Paint the Octopus Red, strove to write this book from a child’s point of view on what having a younger sibling with Down syndrome could be like.” -suggested by Hannah Schoonover GENDER A is for Awesome! by Eva Chen: “I really liked this board book about awesome women. I really enjoyed the quotes by Amelia Earhart, Katherine Graham, Queen Elizabeth I, and…you! Each page features an incredible woman and has a quote by her. I really liked that quotes are included, and they are so beautiful! The illustrations will easily capture your reading buddy’s attention and keep yours. It’s primarily for the 0-4 age range, but I think it would be engaging for kindergarten and first grade students, too!” - suggested by Hannah Kraxberger 50 Women in Science by Rachel Ignotofsky: “Fifty women, born from 350 CE through 1977, have their stories and inventions and experiments recorded in this book. You’ve got your (now) well-known Katherine Johnson, Marie Curie, and…SURPRISE! Did you know that Hedy Lamarr, star of Hollywood’s Golden Age, was also an inventor? She’s most definitely more than just a pretty face. Each biography has an illustration of the woman, a quote from her, a small summary of what she’s accomplished, and a full page detailing how and when she made her mark on science. With all that information, it’s definitely not a sit-down-and-read-all-at-once kind of book, but highly worth your time. This book will be in my classroom for sure.” - suggested by Hanna Kraxberger CULTURAL The Proudest Blue by Ibtihaj Muhammad: “It’s the first day of school and Faizah’s older sister Asiya gets to wear the most beautiful deep blue hijab she has ever seen. It’s a big deal because it means Asiya is all grown up now! But Faizah doesn’t understand why some kids at school tease her sister for the hijab. Don’t they know it is an honor? Don’t they see the beauty in it? Written by an Olympic medalist, this book explains the meaning of the hijab to the Muslim faith and to the women who wear it. The colors and illustrations used are eye-catching for the reader (and listener!) to engage with. Moreover, it tells a wonderful story of being brave, resilient, and understanding of differences. “ - suggested by Hannah Kraxberger Same Same but Different by Jenny Sue Kostecki-Shaw: “A tale of two pen pals, this is a book of exploring differences! Elliot tells about his American house. Kailash writes a letter back about how his house in India is different, but also the same! Kailash writes about his pet. Elliot writes back to share about his pet and how it’s different. As the letters go on, the boys find that same and different are things that they share – in a lot of aspects!” - suggested by Hannah Kraxberger We Are Grateful by Traci Sorrell - “This book walks through memories of the Cherokee people using the native word for “grateful” to apply to different situations as a way of remembering the past and celebrating the future. Side note – This was perhaps the first book I’ve had the pleasure of reading that involved Native American tribes in a non-Pilgrim perspective or setting and it was so good.” - suggested by Hannah Kraxberger While we know that this list doesn’t even begin to scrape the surface of all of the incredible books available to teachers, we are excited about this list because it contains books that have been vetted by actual teachers in actual classrooms.

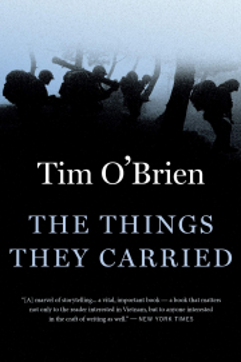

If there’s a book you feel passionately about that should have made the list, comment it below so that we can continue to celebrate and include the voices of both Black culture as well as other minority groups. Happy February and Happy Black History Month! By Erica Shook  Though I am a vocal proponent of getting more contemporary YA lit. into the hands of our students, I do still enjoy teaching some of the classics. The balance in my classroom has come from connecting classic and contemporary works. For example, after we read Beowulf together in class, students choose from four different contemporary novels that they read together in small groups and then connected back to Beowulf (Kendare Blake’s Anna Dressed in Blood, Moira Young’s Blood Red Road, Marie Lu’s Legend, or Neal Shusterman’s Unwind). As an avid reader, my brain is constantly looking for text connections. And with increasing frequency, I find myself connecting current events to texts as well. The current reality for teachers has caused me to do just that. I have adapted what follows a bit because I originally wrote and presented it to our school board to try to build empathy among them for the load teachers are currently carrying. That is what English teachers do, right? Use writing and books to build empathy? The message, however, remains the same. Much like the soldiers in Tim O’Brien’s book The Things They Carried, what teachers carry is partly a function of experience, partly a function of specialty, and partly born of necessity. We carry a veritable rainbow of Expo markers--some that work well, some that we are trying to squeeze the last bit of ink out of; notebook paper; construction paper, printing paper, butcher paper, card stock, poster board; glue; scissors; duct tape, scotch tape, masking tape, painters tape, packaging tape, book repair tape; lab supplies; paper clips; pencils, pens, markers, sharpies, crayons, colored pencils; paint; bulletin board border; rulers; kleenex; band aids; Post-it notes; keys; white out; rubberbands; staplers; index cards; note cards; popsicle sticks; candy; books, books, books; computers, charging cords, cables; granola bars; crackers; chocolate; hand sanitizer, Virex, masks; gallons of coffee; water bottles with times on the side to remind us to stay hydrated; stacks and stacks of papers to grade; and, Flairs in every color. I won’t bore you with the precise weight of each of these items, but know that combined, these things are heavy--and we probably paid for most of them out-of-pocket. As with O’Brien’s characters, the things teachers carry, though, are both literal and figurative. We also carry the professional development that we don’t have time to work with and implement; field trips we can’t experience; technology that doesn’t always work; lesson plans that implode because they were better on paper and have to be reworked on the spot; our own families that don’t always get our full attention when we are at home; dusting, laundry, and dishes that sometimes pile up; continuing education credits; students in our classrooms who struggle (both academically and emotionally) but whom we don’t have time to work with one-on-one; hundreds of decisions every hour--many of them split second; students who are suffering because of bullying; students who are hungry or tired; students who are neglected or abused; students who have lost loved ones or friends; students who feel they can’t share their true identity; students who rarely see themselves reflected in curriculum; students’ failures; students’ successes; students’ smiles; students’ tears; students who have been lost in accidents; students who have contemplated suicide; students who have taken their lives before they’ve really had a chance to live them; and, more love than any human heart should be able to hold for every single one of them who ever passes through our doors. The weight of these things is incredibly heavy. Sometimes almost unbearably so. But we carry it because we love what we do, and we love our students. It genuinely is who we are. But this year, we also carry the weight of students in the classroom and at home with technology that glitches or crashes; catching up students who missed class or missed parts of instructions because of those glitches and crashes; students and staff in quarantine; finding ways to provide equitable opportunities to in-person and remote students alike; students embarrassed to turn on cameras or too shy to unmute microphones; lost instruction time for more sanitizing; the endless, endless emails; the extra prep needed to make sure students at home have the materials they need ahead of time to actively participate in class; time spent converting curriculum to digital versions of itself; learning new tools to do so; needing to collaborate with colleagues with no time to do it; building the relationships and giving the hugs our students need while maintaining social distancing to keep everyone healthy and at school; knowing social-emotional needs are not being met; understanding why some of our students have chosen remote learning but missing having their masked faces in class with us; helping our own children be successful with their learning; the overwhelming guilt for the things we know are necessary but are beyond our ability to do; balancing it all; balancing the emotions; the all-encompassing exhaustion; and listening to one person after another tell us we can’t pour from an empty cup when we rarely have a chance to fill it or suggesting what we need is to take a mental health day with no understanding that the things we carry never get lighter for having done so--it just buys us a bit more time before we collapse under the physical, mental, and emotional weight. Kansas is already experiencing a teacher shortage it will take years to get ahead of, and many more will leave the profession this year, maybe even at the end of this semester, because of the toll the weight of the things they carry is taking. I am concerned for Kansas teachers and the sustainability of our situation. I wonder, as the decision-makers in districts are meeting, whether they have gotten into classrooms to experience the current teaching reality? I don’t mean walk-throughs. I mean, have they spent entire class periods or days in multiple content areas to truly understand the new workload? I want anyone who reads this to know I see you--KATE sees you--and we know how hard you are working for your students. KATE is thankful all year long for Kansas teachers, the magic they bring into their classrooms every day, and the passion with which they teach Kansas students. My hope is administrators, school board members, legislators, and other decision-makers keep in mind the immense weight of the things our teachers carry.  About the Author Erica Shook is the English Department Chair at McPherson High School, USD 418, and a 2020 LEGO Master Educator. Because of her passion for students, educators and education, ELA, YA literature, and social activism, she is also a Project LIT Community chapter leader, LiNK Adolescent Lit. CoP Leader, and the KATE Vice-President. Follow her on Twitter at @Ms_Shook or on Instagram at @ms_shook for book suggestions to build classroom libraries or for continued professional development.  This year, KATE is pleased to announce that on November 7th at 2 p.m., Nic Stone, author of the New York Times bestseller, Dear Martin, will deliver a virtual keynote address followed by a Q&A session, available to all KATE members as our gift to you for your continued support and dedication to teaching English in the state of Kansas. Nic Stone is an Atlanta native and a Spelman College graduate. After working extensively in teen mentoring and living in Israel for several years, she returned to the United States to write full-time. Nic's debut novel for young adults, Dear Martin, was a New York Times bestseller and a William C. Morris Award finalist. She is also the author of the teen titles Odd One Out, a novel about discovering oneself and who it is okay to love, which was an NPR Best Book of the Year and a Rainbow Book List Top Ten selection, and Jackpot, a love-ish story that takes a searing look at economic inequality. Clean Getaway, Nic's first middle-grade novel, deals with coming to grips with the pain of the past and facing the humanity of our heroes. Nic lives in Atlanta with her adorable little family. In lieu of this exciting keynote speech, KATE wanted to provide its members with a little preview of Nic's personality and flair. Cue a hilarious and telling game of "Would You Rather...?" between the author and KATE's VP, Erica Shook. Please enjoy the following tidbits that Nic was so gracious to share with us, and we hope you'll join us on Saturday! Shook: Ok, Nic. Would you rather:

Potter or Snape Stone: SNAPE ALL DAY EVERY DAY. Shook: Know it all OR Have it all? Stone: Definitely have it all. Knowledge can be burdensome. Shook: Talk like Yoda OR Breathe like Darth Vader? Stone: Like Yoda, speak I would. Shook: Be a superhero OR Be a famous singer? Stone: I am CLEARLY both. Tuh. Shook: Go to work OR Stay home and bang on drums all day? Stone: Drums. Shook: Be transported to a place and time of your choosing in the past OR Be transported to a random place and time in the future? Stone: Def place and time of my choosing in the past. Shook: Steal honey from a bear OR Steal honey from a beehive? Stone: I'll take the bear. Shook: Be 50% good at everything OR Be 100% good at one thing? Stone: 100% good at loving people! Shook: Jump into a pool of lava OR Jump into a pool of freezing water? Stone: I mean I die either way, so... Shook: Be stuck inside on a good day OR Be stuck outside on a bad day? Stone: Inside. Sleep is always an option. Shook: Be color blind OR Have no taste buds? Stone: Yeeks... color blind. Shook: Always say everything on your mind OR Never speak again? Stone: Always say everything. (These are brutal.) Shook: Have the power to read minds OR Have the power to read hearts? Stone: I wanna read hearts. Shook: Fight 100 duck-sized horses OR Fight 1 horse-sized duck? Stone: 1 over 100. Even though a horse sized duck sounds terrifying. Shook: Live in a space station OR Live in a deep-sea submarine? Stone: Space station! Shook: Pop OR Soda? Stone: Eww neither. Coke. Sprite. Fanta. Pepsi. CALL IT BY ITS NAME. Shook: Chili and cinnamon rolls OR Chili and cornbread? Stone: Cinnamon rolls. #dessert Shook: Lose the ability to read OR Lose the ability to write? Stone: How dare you! Not choosing. So there. Shook: Lipstick OR Earrings? Stone: This is getting worse and worse. (Earrings.) Shook: Lipstick OR Shoes? Stone: And here I thought we were friends. Smh. (Shoes.) Get registered if you haven’t already. You are not going to want to miss KATE in conversation with Nic Stone. See you all Saturday! Erica Shook, KATE Vice-President By Cheryl Poage As an educator, I have always encouraged my students to go out of their comfort zone and challenge themselves—to reach out and stretch just enough to feel a little discomfort. Over the past 17 years, I became comfortable with my content, my school family and my students—quite honestly, I was perfectly happy in this comfort zone. So when my husband proposed moving back to his home state of Kansas, I heard myself telling my students to “challenge themselves and stretch a little”—and decided it was now my time to stretch! As I began my job search, one position that stood out to me was a Blended Learning position teaching high school English at Andover eCademy. I had never taught high school English, I had never taught online, and seeing the faces of my students every day was extremely important to me! So why choose this? Because it made me stretch…it was a limb I had never reached out to before. What type of educator would I be if I challenged my students to explore the unknown, but wasn’t willing to do that myself? I secured a position with eCademy and anxiously awaited my August 2019 start date. I knew there would be a learning curve on my end, but the challenge intrigued me; this opportunity would allow me to look at education through a new lens. I had so many questions about the Blended Learning Model and it seemed my list grow longer each day: How will I build solid relationships with students? How will I develop a learning community that will allow students to engage in discussion and share learning experiences? How will I give proper feedback when each student is working at his/her own pace? As the year progressed, I was able to eliminate many of the questions I started the year with; however, each brainstorming session with colleagues posed a new challenge—adding to my evolving list. eCademy is fortunate to have an administrator who encourages his staff to be innovative and allots time for collaborative brainstorming sessions. This practice inspired me to refine my craft and become more flexible and open to a new way of teaching and reaching students. Relationship Building The first day of school is always exciting! It is when I am able to put a face to each name on my roster and begin to build relationships. However, this isn’t necessarily the case when teaching virtually. Not every student begins class on the same day and many do not feel comfortable showing their face, so it is important to become creative with lessons and build trust. One modicication I made in order to “see” students in my reading class was to ask students to submit a “selfie” that incorporated a portion of their face with the cover of a novel they were reading. An adjustment I made in a writing lesson was to have students use audio to give a verbal reflection—allowing me to at least hear my students, if I could not see them. These were very small changes, but it allowed me a quick glimpse—it was a starting place. As the year continued, relationships grew through daily feedback, emails and phone calls; however, the most significant difference I saw was when CoVid-19 changed our world! I used the time for reflection and self-growth and revised my teaching even further. I took trainings that were offered, solicited the help of colleagues a bit more and found ways to personalize my lessons to allow student’s choice, time to reflect, and share more of themselves with me through “Motivational Monday” lessons. I scheduled individual and group Zoom sessions for students to work on assignments with me or with peers. I held daily Zoom check-ins with students who were struggling with motivation during the Stay At Home order. I began to see more faces and the trust began to build! CoVid-19 may have taken some opportunities away from us, but it allowed me the time to grow as an educator and it brought many of my students out from behind the computer screen and into a Zoom session! Although the road to building bonds looked different than it did in my previous years of teaching, I do believe the gradual growth was critical to form the foundation needed for solid relationships. Student Success At eCademy homeroom is taken to a new level. Each teacher has his/her own group of approximately 20 students to support. Teachers contact their students on a weekly basis to discuss grades, celebrate successes, and discuss a plan of action for those who may be struggling. In addition to working with our homeroom students one on one, we also have bi-weekly meetings with administration and guidance counselors built into our schedules. During this time we discuss each student’s progress and prepare a personalized plan of action for any student who may be struggling. Our roundtable discussions allow us develop a clear understanding of the overall student. During these meetings, It was inspiring to see how well the teachers, administrators, and counselors knew ALL students—both academically and emotionally. So often, in a Brick and Mortar it is difficult to allot time to engage in these valuable whole group discussions due to scheduling, teaching, non-teaching duties, etc. As a result of these meetings, we are able to focus on students who have consistent missing assignments and a lower than average GPA and create an engagement plan to help them succeed. Students, parents, and the homeroom teacher work together to develop this plan for success. I saw the impact of these meetings firsthand as I worked with several students, via Zoom, during second semester. Not only did these students go from failing grades to passing all subjects, but they also developed a more positive mindset and sense of confidence as they watched their GPA and comprehension of each subject improve. Community What sets eCademy apart from many other online schools is that we follow a Blended Learning model. This is what truly interested me about eCademy and what, I believe, brings in such interest from families across the state. Blended Learning allows students the opportunity to be a part of a school community, while learning at his/her own pace. Andover eCademy offers students numerous opportunities to be a part of a learning community at all grade levels. Students participate in Live Lessons with their teachers and classmates, attend field trips, and participate in clubs or in-house days offered at our Andover campus. In-house days may include group activities, team building, study sessions, guest speakers, or collaborative work. This time allows for students to build community and gain a sense of belonging. High school students have their own special spot nestled inside the eCademy building called the eCafe. The eCafe is situated similar to a coffee shop where students are able to study, collaborate, socialize, and develop friendships. It is monitored by a different high school teacher each hour, allowing students to work personally with the teacher on call. High school students also have the opportunity to plan socials, participate in Science Labs, attend field trips, and a select group also serve as mentors to our middle school students. In an effort to give out of town students the opportunity to build community, we also offer a Mobile eCafe. Once a week a teacher travels to a different library in the surrounding areas and students are invite to come in for a study session. This allows us to meet students who might not be able to travel to Andover, but would like to build relationships with their teachers and peers. Grading/Feedback Giving student feedback is a big portion of each day at eCademy. All lessons are loaded at the beginning of the semester and the courses are self-paced, so we receive various assignments from numerous students in several different classes at any given time. Although the amount of assignments coming in can sometimes seem overwhelming, there are a variety of assignments being turned in which keeps the grading fresh and interesting. Detailed feedback is critical when teaching in an online environment. Since we do not hold daily face to face lessons, feedback is a dedicated time to give each student the guidance needed to master a concept and communicate clear guidelines for students to reference when revising assignments. We offer feedback in several formats: verbal, written and face to face. I have found that since students in a Blended Learning environment are self-paced, they do not experience time constraints that are sometimes found in the classroom. This results in resubmissions and revisions that demonstrate improved execution, comprehension and overall grades. As year two begins, I feel reignited as an educator. The past year allowed me to experience one of the greatest learning adventures of my career. I learned it is okay to start small and grow gradually. I learned that even if a student isn’t right by your side, remarkable relationships can still develop. Most importantly, I learned that education isn’t about being comfortable…it is about change, challenge, and having the confidence to climb out of our comfort zone and STRETCH!  About the Author Cheryl is beginning her 19th year of teaching. In addition to English, Cheryl has taught AVID and served as an AVID Coordinator for eight years in Florida. She is currently a College and Career Elective teacher at Andover eCademy. Her passion is building relationships with her students and changing “I can’t” mindsets into “I can.” By Dr. Katie Cramer As a teacher educator, I have been preparing future middle and high school English teachers—first in Georgia and now in Kansas—for more than a decade. Since 2007, I have used position statements from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) to support my professional practice, particularly my decision to center sexual and gender diversity in my curriculum. When NCTE passed the Resolution on Strengthening Teacher Knowledge of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Issues in 2007, I was able to further defend my curricular inclusion of sexual and gender diversity in my English methods class against resistance from a small but vocal minority of my teacher candidates who argued that …

Aside from expressing my dismay at each of these claims (and my absolute horror at the last one)—as well as my relief that I’ve not heard teacher candidates express these views in the past 10 years—I will not belabor them. In fact, I have written about these challenges before, including in Kansas English (Mason & Harrell, 2012) and more recently in a chapter in Incorporating LGBTQ+ Identities in K-12 Curriculum and Policy (Cramer, 2020). Instead, in this piece, I want to remind all of us that we can be even more powerful in our teaching for social justice when we seek out support from our professional organizations at the state and national levels. What are position statements? For the past 50 years, NCTE has published position statements on a number of issues that guide and support our professional practice. According to NCTE, position statements “bring the latest thinking and research together to help define best practices, offer guidance for navigating challenges, and provide an expert voice to back up the thoughtful decisions teachers must make each day” (NCTE Position Statements). They begin as resolutions, crafted and submitted by a group of at least five NCTE members and reviewed by the NCTE Committee on Resolutions before being discussed and voted on at the Annual Convention and later ratified by NCTE membership. NCTE notes the value of both the process and the product on its resolutions page: “When a resolution is ratified it signals to members and the wider education community that these issues are top concerns. Most resolutions also come with research about and suggested solutions to the problem. As such, a resolution is a tool you can use as an educator to advocate for these issues, knowing you have the backing of a national organization in your stance.” (NCTE Resolutions) The oldest position statements NCTE lists on its website were discussed and voted on at the NCTE Annual Business Meeting in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1970 and include fascinating and still relevant resolutions on …

More recently, NCTE membership has ratified statements that center sexual and gender diversity. During LGBTQ Pride Month, let’s turn our attention to two position statements that support our efforts to recognize and affirm sexual and gender diversity in our schools and curriculums. Resolution on Strengthening Teacher Knowledge of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Issues (2007) NCTE’s Resolution on Strengthening Teacher Knowledge of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Issues was ratified in November 2007 at the beginning of my career in teacher education, and it has provided the support I needed to center sexual and gender diversity in my teacher preparation curriculum. It states that “effective teacher preparation programs help teachers understand and meet their professional responsibilities, even when their personal beliefs seem in conflict with concepts of social justice” (NCTE, 2007). It advocates for the inclusion of LGBTQ+ studies in teacher education programs, even going so far as to advocate that accrediting bodies recognize the importance of the study of LGBTQ+ issues in such programs. This resolution/position statement not only strengthened individual faculty members’ rationales for the inclusion of sexual and gender diversity in their coursework, it also led to positive changes within the NCTE. Less than two years later in March 2009, English Journal published its first themed issue on sexual and gender diversity, and more recently, the NCTE formed the LGBTQ Advisory Committee on which I am currently serving my second term. Statement on Gender and Language (2018) In 2018, NCTE members ratified the Statement on Gender and Language, which evolved out of NCTE’s previous position statements on gender and language from 1978, 1985, and 2002. The most current iteration of this statement “builds on contemporary understandings of gender that include identities and expressions beyond a woman/man binary” (NCTE, 2018). This 12-page document—one of the longest NCTE position statements I’ve encountered—features a plethora of information to guide teachers’ understanding of gender diversity. It defines gender-expansive terminology; describes research-based recommendations for working with students, colleagues, and the broader professional community; and includes an annotated bibliography of resources to help us “use language to reflect the reality of gender diversity and support gender diverse students” (NCTE, 2018). Stay Tuned … This summer, I was invited by the NCTE Presidential Team to collaborate with colleagues across the U.S. to revise three statements on gender and gender diversity. Two of the statements are 25 and 30 years old, respectively, and they need considerable updating as conceptions of gender and sexuality—and the language we use to describe them—have evolved (and continue to evolve). This committee, under the leadership of Dr. Mollie Blackburn, is currently planning to address both sexual and gender diversity in curriculum design in our revisions, and we hope to have one or more statements ready for discussion and vote at the 2020 NCTE Convention, which will take place virtually this year. Your Next Steps I invite you to take some time this summer, as you reflect on your curriculum design and prepare for the next academic year, to engage in the following activities:

Alongside our state affiliate the Kansas Association of Teachers of English (KATE), NCTE’s vision is to empower English language arts teachers at all levels to “advance access, power, agency, affiliation, and impact for all learners” (NCTE About Us). NCTE’s position statements are just one of the many ways the organization enacts that vision. References Cramer, K.M. (2020). Addressing sexual and gender diversity in an English education teacher preparation program. In A. Sanders, L. Isbell & K. Dixon (Eds.), Incorporating LGBTQ+ identities in K-12 curriculum and policy (pp. 66-111). IGI Global. Mason, K. & Harrell, C. (2012). Searching for common ground: Two teachers discuss their support for and concerns about the inclusion of LGBTQ issues in English methods courses.” Kansas English, 95(1), 22-36. NCTE (n.d.). About us. https://ncte.org/about/ NCTE. (n.d.). Position statements. https://ncte.org/resources/position-statements/ NCTE. (n.d.). Resolutions. https://ncte.org/resources/position-statements/resolutions/ NCTE. (2007, November 30). Resolution on strengthening teacher knowledge of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) issues. https://ncte.org/statement/teacherknowledgelgbt/ NCTE. (2018, October 25). Statement on gender and language. https://ncte.org/statement/genderfairuseoflang/  About the Author Katherine Mason Cramer is a former middle school English teacher and a professor of English Education at Wichita State University. She has been a KATE member since 2010 and an NCTE member since 2000. She serves on the KATE Executive Board, and has served as Editor of Kansas English since 2017. She can be reached at Katie.Cramer@wichita.edu. By Amanda Little  Robert Frost is quoted as saying “Poetry is when an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found its words.” It is cryptic quotations like this one that often make people run from poetry screaming. While I identify with Frost’s quip as an amateur poet and an aesthete myself (full confession, I had to look that word up), I can understand why poetry has a tendency to scare off students and teachers alike. One of my main goals, however, is to bring a love of poetry back to my students. Or at least make it so they don’t groan in anguish any time someone utters the word. I have used various methods in the classroom to try and make poetry more accessible for my students. Aside from reading a poem a day out of the critically acclaimed Poetry 180: A Turning Back to Poetry, I try to disarm the word daily. When I start talking about poetry in depth, which is usually sometime around National Poetry Month, I often hear one of two things: “Really?! Ugh!” or crickets chirping louder than those found on a pastoral night in one of our beloved Kansas prairies. But I then ask my students if they enjoy music. Usually, most hands go up or heads nod in assent. Then I drop the bomb. Music. is. poetry. (Wait, whaaah???) I remind my juniors of our Native American Literature unit, of the fact that the oral traditions of most cultures were often first sung around a fire, set to a rhythm to bring it to life and to help them remember their sacred legends. I explain to them that the iambic foot is so widely used in poetry because it mimics our own heartbeats. duh-DUM, duh-DUM, duh-DUM. Poetry is a part of our very being and body. I assure them that most poets aren’t trying to hide a “special” or “deeper” meaning in the words of their poems. That readers connect with some poems and poets more than others. That to a certain degree, a reader gets to connect with each poem in their own unique way. And I comfort them with the knowledge that all a poem is is an astute observation about a microscopic slice of life. Finally, after we’ve taken the fear out of poetry, I introduce them to poet Taylor Mali’s poetry game: Metaphor Dice. Because many teenagers either lack the words or the experiences to put life into lyrics (well, most of us adults do, too, for that matter), Mali, former-teacher/SLAM poet/advocate himself, invented a game to help us identify and connect words with life. He has a starter set and the new “Erudite Expansion” pack. I stumbled across these as I was fan-girling and stalking Mali’s Facebook page—Mali has been a favorite of mine since discovering him in college. (And I continue to follow him. #Noregrets!) You might know Mali for his poem “What Teachers Make” found in his collection, What Learning Leaves. I usually use Mali’s dice as a brain-storming activity for our summative poetry project in which the students must create their own “book” of poetry (usually between 6 and 9 poems depending on the time we have). I give them choices, examples, and mini assignments to help them build different styles of poetry like haiku, concrete poems, acrostic theme poems, and traditional forms (like sonnets). I also let them explore mimic poetry, using an excerpt of Whitman’s “Song of Myself” as the mentor text. I’ve even let them explore slam poetry after viewing a student edition of SlamNation (a 1998 documentary by Paul Devlin). They have quite a bit of freedom balanced with guidance to choose forms and create the poems that will express themselves best. My goal is to help them find their own way to voice their own experiences. And this is where Mali’s dice come in. The way the dice work is simple. In the original edition, there are 12 dice, 4 red (subjects), 4 white (adjectives), and 4 blue (objects). When you roll the dice, you see which subject, adjective, and object make a metaphor that you can identify with. Sometimes you get remarkably insightful ones: Home is a burning kiss. Other times you get hilarious ones: Your mother is a desperate party clown. And still other times you can mix it up by using negation: The world will never be a bright trophy. Once you have found the metaphor that strikes you through your heart, you know you have a poem started. Then the work becomes putting into words why that metaphor is true. Here’s a finished product of my own: Fronts of the Mind Regret is an obstinate odyssey relentlessly pursuing the pursuer memories attacking blindly-- a cyclops, wounded, livid, afraid (but hind-sight is only 20/20 if the view remains unskewed) escape only possible for those with the tools the wherewithal the means still forfeiting friends in the chimerical front that is the mind labyrinthine, snare-filled busy Regret is the perilous sojourn we choose for ourselves knowing we eventually come to the fork in the road realizing we must take the path of self-clemency (the path less traveled) for the sake of our own survival for the sake of survival the sake of sanity the journey of regret must cease and only we choose that for ourselves If you didn’t notice it, my starting metaphor was regret, obstinate, and odyssey. I related to that in my own thought patterns and redemption to create my poem. Many of my own students, especially the ones who thought they hated poetry, have found the days that they played with Mali’s dice to be some of the most fun of the year—I have survey answers to prove it! I have limited sets, so my students work in groups, passing the divided sets from one group to another throughout the class time, which only adds to the conversations and fun. I also pair the dice with Rory Story Cubes to help students brainstorm ideas for their own poetry projects. This year, I am heartbroken that the pandemic is stealing yet another experience from my students, one that this year’s juniors won’t even know they are missing. I can’t wait to get back in my classroom and inspire my unwitting poets next year. In the meantime, I am focused on writing my own poetry. I’ve never been published before—at least not professionally, so I am looking forward to submitting some work and getting valuable feedback from publishers. I find poetry so cathartic, and I hope to inspire that feeling in my students as well. I encourage you as teachers to let your students play with words. We often times are so focused on the analysis and scholarly study of poetry, that it’s easy to suck the joy out of it. And I postulate that poetry should bring joy, both to the reader and the poet. If you are interested in exploring Metaphor Dice for your own classroom, you can find them here or on Amazon. If you would like to know more about my own poetry project, please feel free to contact me via email. I will happily share my resources. About the Author

Amanda Little is a mother of two and a native Salinan who has been teaching ELA and Public Speaking to juniors and seniors at Ell-Saline MS/HS for the last 7 years. She earned her bachelor's degree from Kansas Wesleyan University and recently earned her masters through the summer MA program at Fort Hays State University, graduating Phi Kappa Phi. When she isn't at school serving her students, she is serving through the church, scrolling Facebook far too much, reading books that are past due from the library, and writing poetry. Her first publication was published in the local newspaper when she was in kindergarten, a short poem about Christmas trees. You can contact her via e-mail at alittle@ellsaline.org. By Matthew Friedrichs  As a second-year ELA teacher, there are so many things that I don’t know. One thing, however, that seemed intuitive when I entered the classroom after nearly 20 years as an editor, was the tie between images and words. Great readers effortlessly form mental images as they dance through the words on the page. Unfortunately, many of my eighth-graders, and even some seniors, struggle with that mental animation. At the same time, my photography students in grades nine through 12, often scuffle when asked to translate visual information into words. As a result, I’ve worked hard with both groups to bridge those communication gaps by juxtaposing and connecting visual and written artworks. During the fall 2019 KATE conference, Deborah Eades (@DeborahEades10) presented about using portraiture in the ELA classroom. I could only shake my head up and down in violent yeses as she provided a framework for many of the methods I have tried. Eades shared what she had learned during a Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery training on the topic of stimulating nuanced student conversations guided by pictures. One example of a portrait Eades shared that would spark great conversation in a classroom is Roger Shimomura’s, Shimomura Crossing the Delaware. The painting references the famous image of General George Washington during the Revolutionary War. Close study could be paired with art and/or history classes. The image mixes traditional Japanese styles with pop art and more realistic depictions, and also draws upon Shimomura’s personal history of being imprisoned along with other Japanese-Americans during World War II. Including this painting in my teaching excited me, for while it offers strong, cross-curricular ties, it also offers a deep Kansas connection. Work by Shimomura is on display throughout the state. I am a firm believer that standing in front of art often is more transcendent than looking at an online or print image. Thus, Shimomura, who taught at the University of Kansas from 1969 to 2004, is a great painter for close study and first-hand lessons. These nearby museums hold his works:

In early November, my photography class encountered a Shimomura painting during a visit to the Beach Museum. Martin Cheng: Painter and Fisherman, acrylic on canvas from 1991, fascinated them. They were drawn to the juxtaposition of fishing items, odd text (1+1=3), painting paraphernalia, and the subject’s garb (underwear instead of the mawashi a sumo would wear). Eighth-graders would undoubtedly find it weird, too, a perfect hook for the strangeness they often describe to me in their bewilderment when they read poetry. While I haven’t tried pairing this image in the classroom, the possibilities are infinite. Numbers by Mary Cornish does the math: “I like the domesticity of addition -- / add two cups of milk and stir.” Kansas poet Kathleen Johnson redraws that state connection and highlights the role of sight. “Nothing prepared me for evenings blue as topaz … There’s nothing not stained with color,” she writes in Summer. Finally, since there isn’t space to muse on every line in the canon, Phillis Levin’s Cloud Fishing describes the curiosity that is at the heart of what I teach. “Take care or you’ll catch yourself.” Physical field trips with our students are regrettably shut down right now. However, we do still have the ability to explore both art and poetry. Some of the most famous art museums, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, could serve as a graduate program in history, archaeology, sociology, and even art! for the intrepid and curious person willing to read through the galleries over the period of months necessary to closely scrutinize the tiny portion of its holdings. In addition, artists’ sites such as Shimomura’s, and The Gordon Parks Foundation’s are informative. In this digital age, finding images that contextually pair with readings, literary or historical, has never been easier. Since we shifted to online courses at Marysville Junior-Senior High School, I have been utilizing these online resources to compose a daily email to my English and photography classes. In addition to the links for assignments and our next video class, I connect excerpts from readings, images, Tweets, Instagram posts, and links. As I would do in class, I layer poems, artworks, and my own experiences within these emails in order to provide students a glimpse of the academic path ahead. I supplement the primary materials with some background, usually chosen from details that I think will catch students’ attention. On April 7, I provided a link to a painting by David Inshaw (found on Twitter), which is an illustration of this Thomas Hardy poem: She did not turn by Thomas Hardy She did not turn, But passed foot-faint with averted head In her gown of green, by the bobbing fern, Though I leaned over the gate that led From where we waited with table spread; But she did not turn: Why was she near there if love had fled? She did not turn, Though the gate was whence I had often sped In the mists of morning to meet her, and learn Her heart, when its moving moods I read As a book—she mine, as she sometimes said; But she did not turn, And passed foot-faint with averted head. Like the speaker in this poem, students are consumed with unvoiced longing for a certain classmate to turn their way, to meet their eyes. Our forced seclusion only heightens desires for close companionship, a common denominator of our humanity in all writing. The evocation of an averted head provided hope, to me, that one or more teenagers in the email audience might read and want to know more about the author and painter. As much as students struggle with poetry, when they find the words, the images that resonate with their personal experiences, they embrace the revelation and work to uncover additional meaning. To the reader intrigued by this poem -there’s so much more to explore! Hardy studied architecture and clambered through ruins (which I noted for my blue-collar seniors). I read Tess of the D’Ubervilles, one of his most famous novels, in college but retain only an impressionistic memory of bleakness (a bit of self-deprecation that acknowledges for the “but I’m not going to be an English major” students that even their English teacher doesn’t retain all of the material). Although Inshaw paints the Wiltshire Downs near Devizes, England, not the Sunflower State, we as Kansans recognize open, furrowed fields; the expansive, dark sky and rainbow combination of thunderstorms; the grassy lane with tracks worn by wheels; and a slightly leaning building. Is the painter as pessimistic or sad as the writer? These are symbols, Inshaw’s site says, “not simply of despair, but also of a hope based on a belief in the depth and permanence of all loving human relationships.” Once we return to our classrooms and are cleared for trips, I encourage you to take your students to local museums. Katherine Schlageck and the staff at the Beach Museum work well with educational groups. If artwork you want to see isn’t currently on exhibit, they might be able to pull it from storage. They arranged for us to view photos by Parks -- another Kansas cultural and historical touchstone -- for a visit we made in spring 2019. In the interminable interim, consider what inspires you and your students. Then follow a path similar to the one I walked from Inshaw to Hardy. Search for art that matches your favorite literature and vice versa. What connections do you make? Does an Emily Dickinson poem sprout life when watered with Victorian imagery? Does a Parks photo add depth and nuance to the study of Muhammad Ali? Are there other Kansas artists and writers who foment revolution in your thoughts? I’d love to see the tendrils that intertwine your teaching. Share below your favorite poetry and artistic combinations, the lessons we can learn from them, and what makes them so powerful to you and your students. About the Author

Matthew Friedrichs teaches eighth-grade ELA, senior English and photography at Marysville Junior-Senior High School. He is a 1995 and 2000 KU graduate who is currently a transition- to- teaching graduate student at FHSU. Before teaching, Matthew worked as an editor at ESPN.com and newspapers for almost 20 years. |

Message from the EditorWelcome! We're glad you are here! Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed